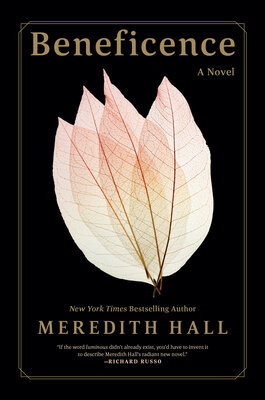

Meredith Hall’s first novel, Beneficence, focuses on the Senters, a farming family in rural Maine over the course of many years. This is a quiet novel, one attuned to both the changing seasons of the natural world as well as the changing emotional landscapes of the characters. It is a novel that considers grief, forgiveness, family, work, and love. Reminiscent of Wendell Berry and Marilynne Robinson, Hall’s writing is truly beautiful. What a pleasure it was to be in the world of this book! We are grateful to Joshua Bodwell at Godine for putting this book into our hands and highly recommend you add Beneficence to your autumn reading list.

Meredith Hall will be the guest of honor at the virtual Literary Lunch with author Simon Van Booy on Wednesday, November 18 at 12:00 pm, hosted by Portland Public Library and Maine Writers & Publishers Alliance.

Literary North: When did the Senter family come into existence for you and how did you decide that you wanted to tell the story from the perspectives of three of the family members (Tup, the father; Doris, the mother; and Dodie, the daughter)? Is it significant that the youngest son, Beston, doesn’t have his own voice in this story? Did you consider having his thoughts included, or did you always know the story would be told from only Doris, Dodie, and Tup’s points of view?

Meredith Hall: After writing my memoir, Without a Map, I knew I wanted to write a novel. I expected that the centralizing idea would be floating close at hand and I would get right down to work. But it took a very long time for me to find this story. It finally came to me as a small bit of conversation with a friend on a snowy day in my driveway. I knew instantly that I had my story: a tragedy of some sort would hit a family, and the husband would behave badly, failing his wife and children when they most needed him. I immediately understood that this would be a study of a man’s selfishness, his self-delusion as he justified his decisions. But that isn’t at all who Tup Senter was. As soon as he started to talk to us, I recognized that the story was not what I had at first imagined. Instead, it would be a study of a deeply attached family having to make their way through extreme loss, and their costly efforts to make their way back to the stronghold of their love for each other and their farm.

From that moment, I knew that other characters needed a chance to reveal themselves to us. I gave Doris and Dodie each a voice. They opened up the story for me—wife and mother, daughter and sister, their powerful identification as family bound by the daily work of the farm. I knew from the start that Beston would not have a voice. I felt that following four distinct voices would be a lot to ask of the reader. Also, Beston was very young at the start of the book, and I believed that readers would want a more adult understanding than he could bring.

But Beston is known to us through the other characters, especially Dodie. She often shares stories about him, and tells us what she knows and understands about this quiet, acquiescing boy. Ultimately, she is forced to mother him, and she reports him to us as a mother would her child. I relied on Dodie to bring us to care about Beston.

LN: As you sat down to write Beneficence, what ideas or questions were in your mind?

MH: The overriding issue of Tup’s personal character, my desire to reveal him in his self-concerned decisions and self-justifications, drove me to this story at the start. That interest lasted about four pages! I quickly felt Tup slipping away from me and determining for himself what the real questions of this book would be. He tells us early in the book, “I am a good man.” And Doris tells us that she is a good mother. But both of them express fear, a foreboding or dread, that something will arrive in their life and they will fail at their love, for each other and their children. I wanted to watch these good people as they struggle against tragedy to redefine themselves and the nature of their loyalty and faith in each other and all goodness.

LN: The Senter farm itself—its chores, its seasons, its joys, and its hardships—seems like another member of the family. Why did you decide to set the story on a farm? How do you see the setting as being integral to the telling of this particular story.

MH: I did not grow up on a farm, although Northern New England farms are familiar to me. I grew up keeping sheep with my sister, and, with other families in my area, raised sheep and chickens and big gardens while my children grew up. I think I have always felt a deep longing for the farm I wrote for the Senters. I feel a powerful nostalgia, a hunger, for a life I never had. I love the Senter farm, and left it at the end of this book with a lot of regret. I feel something like homesickness when I am there with Tup and Doris and their children. So it was wonderful to wake every morning during the writing of Beneficence and feel almost as if I were going home. I am actually thinking about returning to this family and writing another novel, focusing on Grace or Beston.

But beyond my deep sense of the reality of this place, the family is shaped by the land they work as much it is shaped by their hands. None of these people could imagine themselves separate from their farm—the barn, the pastures, the orchard and pine hill, the creek, and the house itself. Several generations of Senters have husbanded this land. Tup and Doris and the children retain that powerful sense of belonging, of being defined by the land and its work.

LN: Your novel has the most beautiful descriptions of light that we have ever read. Was this focus on light deliberate? It feels like a counteractive to the grief in the novel.

MH: It pleases me very much that readers might feel the effect of that focus. It was not deliberate. I was unaware of my attention to light as I wrote. Now, from outside the writing, I can see that light plays throughout the story.

But I pay close attention to light in my own days, and to beauty, so inseparable from light. I can see now that my gratitude for that gift, our strange and mysterious ability to perceive and love beauty and light, inevitably found its way to the page.

And I agree that light relieves us of the weight of grief, or fear, or regret. I think that each of the Senters felt that grace. Dodie is filled with calm as she describes the light in the upper lofts of the barn, or on the rocks and water creatures as they swim in the creek, or the moonlight bath of silver the night they go smelting. Doris loves the big blocks of sunlight that lay across the bedroom she shares with her husband, and the tender lamplight in the front room when the family rests together in the evening. Tup knows the rhythms of light through the day and night in his barn, and the welcome of the kitchen lamp by the sink when he comes in from his work at the end of the day. Light comforts and eases them.

LN: There is such a contrast between Doris (who came to the farm from the outside), who wants so desperately to keep the outside world from her home and family, and Tup (who grew up on the farm), who tells her, “You have to let the world into their home...Nothing good will come of your holding too tight to them.” Where does this contrast come from? Is it their personalities, or their experiences, or something else?

MH: This is a wonderful question, and I have had to think about it. Tup and Doris have both known loss of parents, but their lives have been graced beyond that. I don’t think they are expressing fears born of experience.

Doris has found something so vital in the land and the old house it becomes for her a sanctuary, a stronghold. Her fierce protectiveness of her children extends to a sense of protection of everything that binds them, a deep and troubled awareness of harm that might come.

Tup has always lived on this farm, and has done its work since he was very small. It is as familiar to him, as much a part of his body, as his hands. He left as a young man to go to college, but returned in full faith of the farm’s rightness and generosity. Tup, in many ways, has more faith in the world than Doris does. He trusts more than she does. Doris’s strength and capability belie a fragility that she senses. Ir causes her to doubt the permanence and invincibility of their lives together. Tup trusts and takes for granted that permanence. Each of them react to tragedy from those inner landscapes.

LN: What does your writing practice look like and have you been writing during the pandemic?

MH: I love to write. It feels drug-like, a state I can enter and don’t want to leave at the end of the day. I love making a story, with the possibility that absolutely anything can happen. I sit down to write at 9:00 each morning in my small, welcoming writing room with its big window. I listen to an hours-long loop of Gregorian chants while I write. I have done this for so long now, the moment I click the music on, I feel myself swoop down into another world, my creating world, apart from everything I know in my daily life. And the writing opens.

I wrote deeply for the first several months of the pandemic, but sending Beneficence into the world is taking a lot of time, and so my writing is quietly waiting for me.

LN: Have you read any novels this year that have had an impact on you? If so, which ones and why?

MH: I always like to talk books!

Have you read Andrew Krivak’s The Sojourn? This is not a comfortable read, but it is really powerful. His control over time is extraordinary. It is a slim book but feels like an epic.

Yiyun Li’s first novel, The Vagrants, is stunning in its rendering of characters in a small town in China. Li reveals their fears and capitulations to power and history, their loves and compromises, their losses and silences, in a story which allows us into the intimacy of their homes and the harsh demands of their public lives.

I just reread Marilynne Robinson’s Lila and was knocked over again by her control of the very close narrator. I have studied how she does this and have not figured it out. We are always almost inside her characters, but Robinson never abandons the guardrail of third-person narrative. She draws such full and real characters with so much tenderness and decency. It was a joy to return to the world she created in Gilead and Home.

Thank you. That was a wonderful conversation about writing!

LN: Thank you so much, Meredith. It was a pleasure!

Photo by Nick Brown

Meredith Hall's memoir Without a Map was instantly recognized as a classic of the genre and became a New York Times bestseller. It was named a best book of the year by Kirkus and BookSense, and was an Elle magazine Reader’s Pick of the Year. Hall was a recipient of the 2004 Gift of Freedom Award from A Room of Her Own Foundation. Her work has appeared in Five Points, The Gettysburg Review, The Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, The New York Times, and many other publications. Hall divides her time between Maine and California.