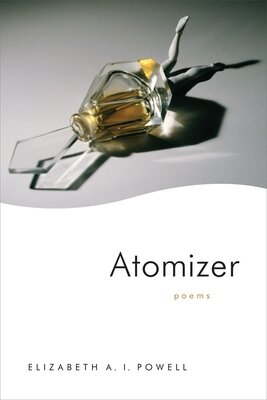

Elizabeth Powell’s third poetry collection, Atomizer (LSU Press, September 9, 2020) is an expansive, honest, and often very funny exploration of life and love in the digital age. Whether she’s writing about the perils and humor of online dating, the insidious workings of capitalism in our cultural and political lives, or her childhood memories of perfume and fashion, these poems are intelligent, accessible, and riveting.

As she says in our interview, “Olfaction gets right into our limbic system, which is what makes smell so evocative and provocative.” And she’s so right. As we read these evocative poems, we remembered the scents of our own pasts: the perfumes and aftershaves, the kitchens and streets, the gardens and forests. Thank you, Liz, for sharing this memorable collection with us!

“…I have inhaled

my worldview from the sterility

of Brutalist architecture, schoolrooms

I have sat in. I am having a smell dialogue

with mold and wet earth and sand

that resides in the woods and playground

inside my memory.”

—Elizabeth Powell, from “The Ordinary Odor of Reality”

Liz will be reading as part of Sundog Poetry Center’s virtual “Two Poets, Two Books” series on November 11, at 7:00 pm. She’ll also be giving a virtual reading on November 18 as part of this year’s Wisconsin Book Festival.

Literary North: The poems in Atomizer are blooming with scents of all types. What drew you to write about olfactory experience?

Elizabeth Powell: Olfaction gets right into our limbic system, which is what makes smell so evocative and provocative. Scent can trigger fragments of recollection, a pastiche of past days, as if conjured by a kind of charmed magic. In this book of poems, I wanted to explore how image is relayed through olfaction rather than sight. I think we as poets can sometimes overlook that an image isn’t always visual, but that imagery can be based upon any sense. I like what the Ukrainian born Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector says in her work Água Viva (it is the epigraph to my book): “What am I doing in writing to you? Trying to photograph perfume.”

I have been drawn to the olfactory experience vis-à-vis perfume since my haunted childhood. My posh Parisian stepmother worked in the beauty industry for a French perfume house. My mother worked in the fashion industry, so, between the two, them I was schooled early and often in the fundamentals of fashion and fragrance. They favored the olfactory art of Bal a Versailles by Jean Desprez, the romanticism of Guerlain, and the abstract expressionism of Francis Fabron’s L’Interdit for Givenchy, but I was a Chanel girl.

Anyway, as a very young latchkey kid, I’d drift down to the perfume shop in the village and follow the congenial and charitable shopkeeper, Ingrid, around. I learned by studying her erudition and easy way with customers, the way she wrote receipts in a fabulous script, the way she winked at certain people when they understood they had, alas, found their scent. I was impressed with the magnificence and artifice of the bottles and labels. So years later, as an adult, when I dated a man who was a bit of a perfume scholar, I was lured in. I began to realize the ways in which perfume and olfaction can gaslight us, tell us different narratives than those that are fundamentally true. Sometimes people call this romance, but that’s a mistake. It’s a kind of violence toward reality.

I mean initially perfume or incense was a way to honor God, but capitalism in the shower-in-every-house world has changed that quite a bit. The perfumes of Baudelaire’s day meant something different than they might now. Don’t get me wrong, I’m all for mystery and romance, but compounded with advertising, marketing, and online dating, it becomes a vehicle for truth distortion, an Orwellian world of love. I hope my poems are a stay against the confusion, my love letter to Truth.

LN: In the title poem, you ask, "Is it right to write about love during the new regime?" and then you proceed to write quite a bit a out love throughout the book. Did you answer your own question? Is it right?

EP: It’s complicated. It’s not a new question by any means. Poet Paul Celan and poet/playwright Berthold Brecht engaged deeply in that dichotomy/quandary and thought discussion. I tend to side with Celan that we must always write about love because it is the thing that makes us most human. Love is a form of human spirituality. Of course, Brecht is correct also that the writer must interrogate the society’s egregious political and social sins. It is the writer’s duty to chronicle the human experience in all forms, each writer from their distinct vantage point and experience. In some ways, our psychological make-ups are per-ordained by the love we did or did not get as our brains and bodies were developing: that is, the political is personal. Sometimes things are not either/or, but instead are and & and. However, it is a question I continue to ask myself.

I can’t help but think that self-realization is a means to general human progress. The great thing about poetry is that it is prescient, sort of psychic. As one writes a poem one must also simultaneously live the experience in order to explore the question. Sometimes poems show you the thing you could not see in your life before. Writing is generative in so many ways, a way to stay alive, and a stay against impermanence.

LN: Many of your poems explore the current state of our country and the humorous and frustrating roles of technology in our lives. What questions were in your mind as you were working on the poems in Atomizer?

EP: Sometimes we must laugh, so that we don’t cry. Humor is a self-protective stratagem, a kind of its own singing and phrasing. There is a thin distinction between laughing and crying, and it is at the core of our human empathy and ability to process intellectual and emotional information. Personally, when writing some of the poems, I was exploring and living into the question of how much human interaction around love and dating has changed so dramatically over the past 25 years. An important book in my thinking about technology and love is the French philosopher Alain Badiou’s work, In Praise of Love. Badiou’s’ central tenet in that book is that love is a philosophical event whose power lies in collaborative ongoingness, love as a production of Truth. Badiou talks about the advent of online dating as eroding humanity into a kind of consumer fulfillment.

LN: One theme we really enjoyed in this book is the way tiny bits of matter make up the whole: the atoms of perfume dispersed by the atomizer, the pointillism dots in a painting, the events that linger as memories. Is this something you thought a lot about before writing these poems book, or did it arise during the process of writing them?

EP: Thank you for that. I am fascinated by the dispersal and reshaping of form. I love to be an amateur observer of physics. It’s important to me to see and appreciate connectivity. I spent a lot of my growing up hanging out with my scientist, science journalist grandfather, and those walks and talks through art galleries with him really captured my imagination. He became a Unitarian to become a better atheist, and from him I learned how science could inform spirituality.

He helped me to see early on what Frost said about the importance of poetic metaphor, how if you can’t understand metaphor, you are lost in history, lost in science, etc. Even though he was a science guy, Frost had influenced him a lot; as a student at Dartmouth in the 1930’s when Frost visited he drove him around. One of my prized possessions is my grandfather’s signed book of Frost’s poems. But, really, I also think my seeing parts in the whole is from suffering from ocular migraines as a young person, and seeing dots, which seemed to be the building blocks of visual space, float about me, endlessly.

LN: Perfume and certain smells seem to invite memories much like the way taste functions in Proust. How does smell influence memory in your poems?

EP: Smell and memory narrate the fragments of our lives we can’t or don’t want to forget. They are the vehicles for nostalgia. One book on perfume I found fascinating is The Secret of Scent, by Luca Turin, who is known for the vibration theory of olfaction. Turin, a perfume and fragrance industry authority, is a biophysicist interested in bioelectronics. In The Secret of Scent he talks about the way in which smell and memory work together in a way I find intellectually pleasing:

“The top notes, the first ones to fly out, say it is still early in the evening that feels full of promise. Next come the heart notes, where the perfumer’s art really shows itself, where fragrance tries (like us) to be as distinctive, beautiful and intelligent as possible. Lastly, by three am the perfume has literally boiled down to its darkest, heaviest molecules at a time when our basest instincts, whether for sleep or other hobbies, manifest themselves.”

That really captures essence (in all its definitions) in regards to perfume.

LN: The poems in this collection really speak to each other, more so than any collection we’ve read recently. What was putting the collection together like? Do you enjoy moving the poems around to get the sequence right?

EP: Poems in a collection are always in conversation, you are so right. I find it an enjoyable exercise to move poems around when putting a collection together to see how they speak to one another. The poet’s job at that point is to eavesdrop on the conversation the poems are having with each other, because that is what will deepen and create greater meaning, It is like fashion, how you can change the feeling of an outfit by letting different pieces speak to one another. Artists do this with images, especially in diptychs and triptychs and so forth. Putting this collection together was difficult on a personal level. Each time I thought the book was finished, some life experience would turn up that I’d have to work to understand and process through the poems. I guess that’s why my mother always said: It is always darkest before the dawn.

Elizabeth A.I. Powell is the author of three books of poems and a novel. Most recent is Atomizer just out from Louisiana State University Press. Her second book of poems, Willy Loman’s Reckless Daughter: Living Truthfully Under Imaginary Circumstances won the 2015 Anhinga Robert Dana Prize, and was named a “Books We Love 2016” by The New Yorker. Her first book, The Republic of Self, was a New Issue First Book Prize winner, selected by C.K. Williams. Her novel, Concerning the Holy Ghost's Interpretation of JCrew Catalogues, was published in the winter of 2019 in the U.K. Her work has appeared in the Pushcart Prize Anthology, American Poetry Review, Brooklyn Vol. 1, The Colorado Review, The Cortland Review, Electric Literature, Seneca Review, West Branch, and elsewhere. She is Editor of Green Mountains Review, and Professor of Creative Writing at Northern Vermont University.