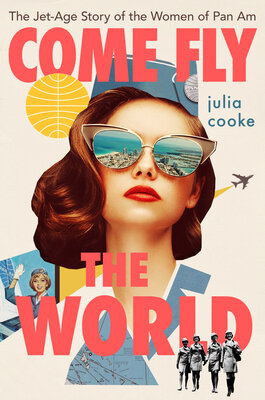

We’ve been eagerly anticipating Julia Cooke’s latest book of nonfiction since we heard about it last year. Come Fly The World: The Jet-Age Story of the Women of Pan Am is out from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt on March 2 and has received starred reviews from Library Journal and Kirkus Reviews. It’s a dazzling book filled with personal stories of the women who worked as stewardesses for Pan-Am in the 60’s and 70’s. From airline dress codes to protocols for dealing with hijackers to Pan Am’s involvement in the Vietnam War, Come Fly the World is packed with fascinating details about the jet age.

The Norman Williams Public Library and the Yankee Bookshop will be hosting a virtual book launch for Julia on March 2 at 7:00 pm. To learn more about future events, please visit Julia’s website.

Congratulations, Julia, on your wonderful book!

Literary North: Do you remember the moment when you decided you wanted to write a book about the women of Pan Am? When did this idea first come to you and what ignited the spark to write a book about it?

Julia Cooke: I met a few former stewardesses at a Pan Am Historical Foundation event at the Eero Saarinen TWA terminal at JFK (before it became a hotel!), which I’d always wanted to visit, since I’ve done a fair amount of writing about architecture. I just loved talking to these women: they seemed to have lived life elbow-deep in adventure, they talked about events of geopolitical history as if they'd had martinis with prime ministers the night before, they were sophisticated and smart and funny. One seventy-something woman told me she rarely bought a return ticket from anywhere because, “you never know.” I loved their attitudes and the way it felt like they owned the world and I wanted to know everything about them.

LN: There are so many riveting details throughout Come Fly the World. How did you handle the research for this book? Was it clear to you what the structure of the book would be like early on, or did that change as you wrote?

JC: The research was slow going at first, since this book is quite a departure from what I’d written in the past, which was mostly based on on-the-ground reporting. A lot of books, from really valuable academic studies to mass-market nonfiction, have been written about the jet age, and those were great help at the start. Though most of them totally ignore the tens of thousands of women who crewed on the planes, these books offered a fantastic jumping-off point for my interviews with the women themselves.

My approach was to toggle between reading a lot, interviewing a lot, going to newspapers and archives to confirm the details around what my interviewees told me, and then going back to the women to ask more pointed questions about the scenes they’d initially told me about. Once I’d found the women who would be my main subjects, whose memories are all very, very good—and who were really honest when they didn’t remember a certain detail—the research was exhilarating. I would hear about some anecdote, whether it was a flight into a war zone or the kidnapping of 19 diplomats off of one woman’s plane, and then read about it in newspapers and history books, and then hear thrilling details about the same scenes.

I always knew that I wanted to write a character-driven book in a close third person, as close to my interview subjects as I could get, but the actual structure of the book itself took a really long time to get to. I think I’ve written each chapter of the book in about four or five different ways, or places, or versions.

LN: The personal stories and quotes shared by Tori, Clare, Hazel, Lynne, and Karen were so compelling and made this story come to life. How did you find the women whose stories you shared in Come Fly the World? Did their stories change the direction of your book in any way?

JC: I found them mostly via Pan Am’s incredible network of former employee and one particular organization, World Wings International, that hosts events for former flight crew. I attended lots of luncheons and reunions, which required some travel—Savannah, New York, Bangkok, Berlin. Stewardesses’ social bonds, by the way, were a real inspiration for me to observe. They prioritize their friendships and take trips together and generally have a grand time.

Their experiences absolutely shaped the book. At first I’d hoped to track down a woman who’d worked with the CIA, a rumor that’s long threaded through the Pan Am community, but I couldn’t really find much on the record. But the women were so interesting that I kept talking to them, and soon a very different book began to take form—one that focused more on Vietnam war flights and on how the job itself acted on the lived experiences of each of the women.

LN: On page 12 you write, “What was revolutionary was the lack of should in this job, the plenitude of could.” In what ways did being a stewardess open up the world for women? What were the lasting effects?

JC: There had never been a job, before, that gave a woman a reason to get out into the world—that was what I found so fascinating about the first stewardesses, that they were all women who had jumped at the opportunity to professionalize their wanderlust. It was dignifying and exciting at the same time. Their new independence was multifaceted: they earned money, spent time away from home, traveled without chaperones, made friends with people who might have come from vastly different circumstances than they.

The way that women’s work has contributed to the feminist movement has always been undervalued, when in reality—as the book argues—stewardesses, at least, moved the needle quite a bit. Not only with the pioneering equal employment lawsuits that some of the bolder among them pushed, but also with the fact of that independence and the way it spirals out into life. It would be difficult to quantify how the empowerment and financial independence of women working in traditionally feminine realms contributed to shaping the world I grew up, its widened opportunities as opposed to what my mother and grandmother were presented with—but it certainly had an impact.

LN: The contrast between the common public perception in the 1960s and 70s of stewardesses as sexy servants vs the actual difficulty of their jobs is stark. At one point, you quote a stewardess who told a reporter, “I think of myself as someone who knows how to open the door of a 747 in the dark, upside down, and in the water.” Do you think that public perception has shifted, or are female flight attendants still fighting the same battles they always have?

JC: I think some of that perception has shifted as flight crews have come to better represent the population at large—which is to say they’re not all female, and they’re more racially diverse. But I think flight attendants are still seen, on some level, as waitresses in the sky, to quote The Replacements. To some extent it’s understandable—the infrequency of flight accidents and emergencies is, after all, a good thing —but really it’s bullshit. Flight crews are well-prepared, well-trained, and able to handle a great many unpredictable outcomes. They also tend to be interesting people who’ve made some unconventional choices in life—that’s why I like talking to flight attendants in the galley sometimes, back when I used to fly a lot!

LN: In your description of the Operation Babylift flight, you use this incredible phrase we can’t get out of our heads: “There was a perverse gorgeousness at work.” Can you explain why you described it that way?

JC: A few of the women I spoke with were very sensitive to what they saw as the gendered differences between waging war and cleaning up after it. The jobs they had performed in the war had shaped this perspective: they had ferried frightened and shell-shocked soldiers around Asia and across the Pacific, sometimes acting as a therapist-slash-cheerleader-slash-girl-next-door, trying to cheer up the men or at least lend a compassionate listening ear. They’d had intimate knowledge of the human consequences of war and a few of the women I spoke with had come to find war in general, and especially this war, utterly repugnant. And yet, when they were given the directive to fly into this war zone because 400 children, many of whom had survived a harrowing crash the day before, needed evacuation—they all jumped to do what they could to help these children.

Later, they, like the rest of the world, would have more complicated feelings about an event that turned out to be much more muddled than an evacuation of legally-cleared, orphaned adoptees. But in the moment, all they’d known was that children needed a flight out of Saigon. And to watch this crew of women leaping in to work together under such circumstances as the Babylift—the way it unfolded was just incredible, so surreptitious, so tragically urgent—was beautiful, too.

LN: You beautifully describe the upstairs lounge on a 747 as a place “designed for coming together en route” that also “felt rich with the awareness of its impermanence.” Is this something you relish in your own travels?

JC: Absolutely. I tend to love everything about travel except for cancelled flights. I’m aware that there’s not much glamour in waiting for a flight in a modern-day airport, or being jammed into a window seat on a crowded plane, but give me any window seat, some moody music, and a nighttime landing over any city, and I’m happy. The sheer transience of the vistas I see out of a plane window makes them valuable to me, really no matter what they are. And I’ve met some amazing people in transit, whether on planes or other vehicles of movement—they’re these strange momentary not-relationships with strangers that are conditioned by the fact of their impermanence.

LN: As literary fiction readers we enjoyed coming across quotes by Mavis Gallant and Olga Tokarczuk in Come Fly the World. How does your reading life influence or shape your writing life?

JC: I found myself reading a lot of peripatetic women writers of various eras over the years I spent writing Come Fly the World—Mavis Gallant and Olga Tokarczuk, but also Sybille Bedford, Martha Gellhorn, and others. Also writing by incredible thinkers and observers of the era I was writing about: Elizabeth Hardwick’s essays, Joan Didion’s reporting. I tend to read around whatever my subject is. I don’t like reading other people’s writing on the same subject except for actual research. I prefer to read writing that sets the tone for whatever I’m thinking about at any given time.

LN: Are there any books coming out in 2021 that you are particularly excited about?

JC: Olivia Laing’s Everybody; Alexander Nemerov’s Fierce Poise, an inventive and wonderful biography of Helen Frankenthaler; and I’d point also to a book that came out late last year that I’m just reading now, Leonard Koren’s Musings of a Curious Aesthete.

Julia Cooke is a journalist and travel writer whose features and personal essays have been published in Time, Smithsonian, Condé Nast Traveler, and Saveur. She is the author of The Other Side of Paradise: Life in the New Cuba. The daughter of a former Pan Am executive, Cooke grew up in the Pan Am “family,” a still-strong network across the globe. She lives in Vermont.