Arisa White’s Who’s Your Daddy (March 1, 2021, Augury Books) is a riveting memoir in hybrid form: a collection of poems, memories, song lyrics, proverbs, myths, and prose that spin the tale of her coming to terms with being fatherless. The book begins in her early childhood and takes us through her search for her estranged father. Along the way, she explores notions of absences and presences, the hide-and-seek of life, and the discovery that fatherlessness does not define who she is.

Arisa’s book is filled with beauty, pain, strength, playful language, and images so concrete and beautifully described that reading her book is almost like riffling through a series of old photos, but photos that include sounds, tastes, smells, and feelings as well. Who’s Your Daddy is “A portrait of absence and presence. A story, a tale, told in patchwork fashion” (p. 112).” A presence indeed. One we won’t be able to forget for a long time to come. Thank you so much, Arisa, for sharing your book with us and the world. Congratulations!

Arisa will be giving an online reading with Dara Wier via Gibson’s Bookstore on March 9, at 7:00 pm.

Literary North: Who’s Your Daddy is a brilliant combination of poetic prose, proverbs, dreams, poetry, quotes, memories and song lyrics. How long did it take to write Who’s Your Daddy and what did your writing process for this book look like?

Arisa White: It took about seven years to write. At first it was a collection of thirty-three epistolary poems addressed to my father, which started as an exercise to prepare myself to actually write a letter to him in Guyana. I was later fortunate to receive a grant from the Center for Cultural Innovation in Los Angeles. The project I proposed was three-pronged: Create a self-publication of the epistles. The self-publication, dear Gerald, was a limited edition printing of 100 and were given in exchange for letters written to estranged, dead, absent fathers and patriarchal figures. Secondly, I hosted community-based epistolary writing workshops. The third part of the project was a trip to Guyana to meet my father and give him a copy of dear Gerald.

Once in Guyana, documenting the whole experience of meeting my father, I now had more information to put to the question of who’s your daddy? As much as I could, I was pulling from all the material of my life, what I was encountering intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually to create responses. It wasn’t until two years after my trip to Guyana, while curating a reading series at the Museum of the African Diaspora, that I was able to harmonize the different registers of voices into a coherent narrator. That summer amongst the visual art, a twelve-page lyrical prose piece gave me the courage to continue writing on. So when I found out that I was going to be moving cross country from California to Maine, I spent the spring semester, while visiting at Mills College, where I had my own office that got such good afternoon light, writing for two-to-three hours after my classes to get a first draft of Who’s Your Daddy completed.

LN: That detail about the good afternoon light is so great. We all know that visual artists require just the right light, but it’s easy to forget how important light is to the writing process too.

AW: Sometimes, after a rain, the light would bounce off the puddles on the roof and make prisms on the wall or ceiling of my office. Moments like that were reminders to play for me, to find ways to bring light into those dense and shadowy memories, and do so in a way that shifts consciousness. A room with light feels so promising, a new beginning, and energizes me when inspiration wanes.

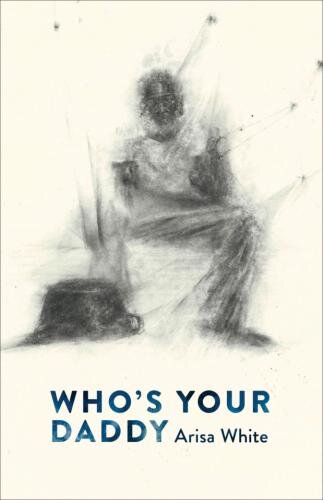

LN: We love the illustration on the cover of your book: “The Drinking Gourd," by Sydney Cain. Could you tell us the story behind it?

AW: A month after submitting the manuscript to my editor, I stepped into Sydney Cain, aka Sage Stargate’s, exhibition Transitions at the African American Art & Cultural Complex in San Francisco. I was taking a break from a dress rehearsal and roamed into the gallery, and “The Drinking Gourd” immediately caught my eye.

An older black man drawn in graphite, on paper, in a sitting position. What looks like a cast iron pot turned over, gossamer lines extending from his body into the sky, making the asterism of the Big Dipper, also known as the Drinking Gourd. There is an African American folk song, believed to have instructed enslaved folks to freedom, and the first verse goes like this:

Follow the drinkin' gourd

Follow the drinkin' gourd

For the old man is comin' just to carry you to freedom

Follow the drinkin' gourd

I was face-to-face with a drawing that felt like the whole experience of writing this book. A process of trying to get free from narratives that didn’t allow me to see myself clearly. And the graphite captured, both texturally and emotionally, that sensation of there and not there. But most startling about the image, it looked so much like my father.

LN: That’s a really powerful story and it’s obvious why you wanted to use the drawing on the cover of your book. Was it easy to get permission to use it? Has Sage had a chance to read the book yet?

AW: It was easy to get permission. I asked Sage Stargate for their contact information when I was at the gallery. My publisher and editor thought the image was perfect for the book and when we were ready for layout and design, I sent Sage an email. I explained my journey of reconnecting with my father and described what the book was about and doing. Sage responded: “Your description is entirely a part of why I use constellations and stars in my work. I believe drawing and writing is how I found my father last year.” It was sweet to know that their art was performing a similar kind of healing. I have recently sent Sage a copy of Who’s Your Daddy.

LN: Each of the four sections of Who’s Your Daddy? begins with a Guyanese proverb. How did you discover these proverbs and in what ways did they shape your work throughout the writing process?

AW: I came across the book Proverbial Wisdoms from Guyana while doing an Amazon search for books on Guyana’s history. What’s nice about the book is that Victorine Grannum-Solomon provides the proverb in creole, the literal translation, and then the meaning in standard English. I’m not sure what I was seeking from these proverbs, maybe sounds, ways of looking, knowing, and being. Images to use. Rhythms and cadences to tap back into. It wasn’t until we were near editing the manuscript that I decided to use the proverbs as section titles. It was a nice way to further expand the book’s motifs and bring more Guyanese presence. I went back-and-forth on whether to include the meanings of the proverbs in the book, but decided that I wanted the images to linger in the reader and as it lingers, its meaning becomes known.

For fun, I will include them here, because the meanings reflect the content of each section:

-

Blood follows the veins: “Children exhibit similar traits to their parents.”

-

The moon runs until the day catches it: “You can take chances, but one day you will be caught.”

-

Woman rain is never done: “A nagging woman can be an endless irritant.”

-

The boat which has gone to the waterfall cannot return: “Some things, once set in motion, may be difficult to change.”

LN: Names and naming are prominent in this book: the pronunciation and meaning of your name, the “bracket of boys” who share the same middle name, the invention of your name, and the inventor (your father), and many other references throughout the book. What is the importance of names and naming to you?

AW: During this span of time I was working on Who’s Your Daddy, I was also writing a middle-grade biography in verse of Biddy Mason, midwife and philanthropist, born enslaved in Georgia or Mississippi, later freed through the Los Angeles court in 1856. She owned several properties in downtown Los Angeles, and became a millionaire by today’s standards. I needed to construct Biddy Mason’s childhood and family life and since such information was not recorded, I researched kinship practices of enslaved folks and first names were a way to pass down the memory of elders and ancestors.

Cynthia Dillard’s Learning To (Re)member the Things We’ve Learned to Forget: Endarkened Feminisms, Spirituality, and the Sacred Nature of Research and Teaching is an amazing book that has made me recognize and embrace the importance of spirit in my creative practice, teaching, and research. Even moreso when you are laboring in the redactions, omissions, silences that is history and the American enterprise, you cannot go on thought alone, off of what’s written down; you need a literacy for the in-between, for what moves you, and the technology for that is spirit. Dillard’s has a chapter devoted to the importance of naming, and in it she writes:

“Within in African culture, naming is a sacred practice, [I’ve underlined this clause and noted “father named me” in the margins] one that is not only important to the continuation of the group’s heritage and work but also to the purpose and future work of the individual being named.” (70)

Growing up, my first name was not a common name for a little black girl. And I felt so othered. I could never find my name on souvenirs. I was so original I wasn’t recognized. Through Dillard’s book, I began to view my father naming me as a sacred practice, which felt like an honor and a gift, which then lifted me out of a sad old story about myself and him and into a far more generative space that deepened the development of my narrator. (Even though I am writing in first person, based on my experiences, I still need to develop a persona that is separate from me. One that can move through space and time in a way that I cannot.) Reading works like Dillard’s, I recalled all the meanings I’ve come across and was told about my name and used those meanings to spark writing, and to create myself into a spiritual being with a purpose that not only served me, but others as well.

LN: At the heart of this book is the notion of absence as a creative force: that the lack of something—a hole or space—creates the shape around it, the negative space revealing the positive space. The word “unhello” in one of your pieces brings that notion out audibly. When did you start thinking about the way absence works to create presence in a positive way? How has that thinking shaped your writing in this book, or more generally?

AW: I started to think this way when my editor Kate Angus suggested that I add more moments from childhood and adolescence. At that time, the manuscript focused on the trip to Guyana, some critical romantic relationships, and a whole thread on toxic masculinity that included a piece on R. Kelly. This was fall 2018, and I recently started a tenure-track position at Colby College, so I remember feeling overwhelmed with the prospect of mining through my childhood and teens to find memories I haven’t already written about. Usually when I find myself in a “cundungeon”—as my wife likes to say—I go to theory and cultural studies to appropriate fresh frameworks for apprehending the thing that evades me. I did a database search and came across this article from the Journal of Family Issues: “When is the Father Really There?: A Conceptual Reformulation of Father Presence,” by Edythe M. Krampe. And when I read the following paragraph, my creativity was powered up:

“…father presence…takes into account the paternal relationship, other family influences, nonfamilial persons, and cultural and religious beliefs that may contribute to the place and meaning of father in the individual’s life. This model of father presence goes beyond the personal father to a social nexus of interpersonal relationships (the father-mother relationship, mother’s support) to cultural and religious belief about the importance of father for the child and family. This best expressed in a context-based paradigm.” (878)

So for my revision, I looked for the father presence in my childhood and adolescence and I also found ways to recreate him through personality characteristics we have in common and shared body features—I look at my feet and hands and see my father. I got to revisit these memories, as they were actually felt and experienced, as a presence and not an absence.

LN: “Cundungeon” is a most excellent and useful word. Speaking of words, one of the things we really love about this book is the wordplay and the insistent rhythm to these pieces, the “schupsing like a rock skip, skip, skipping.” The book really begs to be read out loud. What role does reading out loud play in your writing? Do you write or revise by reading the pieces to yourself or to others?

AW: The rhythm, for me, pulls everything together. The writing has this kinesthetic birth in the body before it gets to the page and I’m trying to language the best wordscore. During the revision stage, I move a lot with the text: turn on the music (I listened to FKJ's “Tadow” and Leon Bridges’ “River” pretty much on repeat), shaking and stretching, walking around my home with a part repeating inside me, letting the motion of my body create a way to move the line or sentence along. I read it out loud to make sure the breath is in the right place and the discord strikes where I need it.

LN: Though the book is about finding a father, the women in your life, and the fact of becoming and being a woman, are central. The very last words in the book are a beautiful image of your mother (and the act of her creative force), “golden like a natal queen.” Can you talk a bit about the role of women in your life and in your writing?

AW: I love women. I was raised by my mother, grandmother, aunts. They are a source of information, inspiration, story, and direction. While in junior high school, I decided to create a class magazine; assign features and columns to my classmates, literally cut and pasted the layout, and my mom took it to her work and made a set of thirty copies for everyone in my class. My teachers were amazing supporters of me as a writer, dramatist, and artist. My English teacher from high school, Nila Grutman, who I am still in contact with today, was the one who encouraged me to go to Sarah Lawrence College for creative writing. My sociology professor Regina Arnold helped me decide that it was an MFA in poetry that I was called to pursue. Chikwenye Ogunyemi, now emeritus professor of literature, whose classes introduced me to the in-depth study of Toni Morrison and black feminist literature, was the one, after coming back from Guyana in 2015, who said that she could see books coming out of this encounter, and “Do try to write something about fathers, if you can do so without bashing them.” So this is what I did. Women tell me what to do and I pay attention.

LN: Our friend, the writer Robin MacArthur, talks about having literary touchstones—books that you always have surrounding you and that you return to often. What are your literary touchstones?

AW: I return to the essays of Audre Lorde and Toni Morrison most often. I started the new year with a promise to myself to read all of Norton’s The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde by February 18th, her birthday. Since I’m reading her work in the order in which it was published, I get to encounter the first poem I read by Lorde—“On a Night of the Full Moon”—within the constellation of her entire work. What is the work before that poem? What is the work after? “On a Night” is so sensual and feminine and this poem captured my emotional experience of being with a woman for the first time. Not only did I feel recognized by Lorde, I was also felt.

A few poems before “On a Night’s” appearance in Cables to Rage, there is the poem “Martha,” where Lorde plainly states her attraction to and relationships with women—through a voice that is addressed to a former lover, recovering from a car accident, Martha. In prior poems and the prior collection, you wouldn’t think Lorde was a lesbian, especially if you didn’t know anything about her. This surprised me. I regard Lorde as the one who transforms silence into language and action, a warrior poet, and reading her work I see that our transformation into language and action is individualized. I realized this most profoundly when I started to create a “Martha” poem of my own, writing to my best friend, and in doing so, I realized how much I don’t say on a daily basis, how much I allow myself to deny my deep feelings. And I was only able to feel this when imagining talking to my friend, feeling like it was a matter of life or death (which isn’t so hard to imagine as black women in the corporate technocracy of the USA during a pandemic); then I was able to feel and feel safe reaching into some deeper stuff. I’m seeing Lorde’s poems as offering ways to position yourself in your own life so you can be closer to your truth.

Arisa White is an assistant professor of creative writing at Colby College and a Cave Canem fellow. She is the author of Who’s Your Daddy (Augury Books 2021), co-editor of Home Is Where You Queer Your Heart (Foglifter Press 2021), and co-author of Biddy Mason Speaks Up (Heyday Books 2019), winner of the 2020 Maine Literary Award for Young People’s Literature. She serves on the board of directors for Foglifter and Nomadic Press.