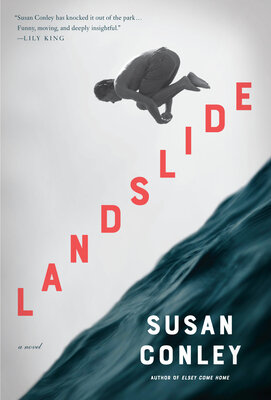

Susan Conley’s latest book, Landslide, is a beautiful, spare novel about motherhood, adolescence, Maine, middle age, and marriage. It’s a novel about the struggles and challenges of living in our current world, but it is also filled with humor, light, and gorgeous descriptions of the sea. It’s a perfectly balanced novel, and because of this, it’s hard to put down. You might find yourself reading this compelling novel in one sitting! Landslide will be published on February 2 by Knopf.

We were delighted when Susan agreed to an interview. Thank you so much, Susan, and congratulations on Landslide!

Susan will be reading from her new book at two local, virtual events. On February 4, Susan will be in conversation with Sarah Blake via Northshire Bookstore. On February 11, she’ll be joined by fellow Maine author Kerri Arsenault via Gibson’s Bookstore.

Literary North: How would you describe Landslide to readers? What ideas were you thinking about when you were forming the story in your mind?

Susan Conley: I like to say that Landslide is about two teenage boys who want their mother to be “sex-positive” and to sing normally to the car radio and not move her mouth in weird ways. The book tells a story about how we survive when it appears we’re in the act of losing everything: our children, our marriage, our livelihood. The book is set on the Maine coast in a fishing village not unlike the one I grew up in, and my greatest hope is that the story honors the inner lives of teenage boys and interrogates what I like to call the vast underselling of boys in our country. Landslide asks how a mother can learn to speak “teenage boy” and to connect with her sons so that she doesn’t lose them. The book also explores what a family is at its most elemental, and how love can endure and if it can.

LN: The novel opens with Jill and the boys in the car when the Fleetwood Mac song Landslide comes on. Did you decide to title the novel before or after you wrote that scene? What does the title mean to you in the context of this story?

SC: We have a joke here in Maine where I grew up that you can’t go a day without hearing at least one Fleetwood Mac song on the car radio. I started writing Landslide while driving up the Maine coast one fall day after the summer tourists had left, and the third Fleetwood Mac song of the morning came on. I sang to myself and laughed about how my two teenage boys will try just about everything to stop me from singing in the car. Then I pulled over and wrote some of the first lines of the novel. Months later, it became clear to me that the novel wanted to be called Landslide.

That word—landslide—had taken on so much resonance in the book. Yes, it was a nod to Stevie Nicks and the nostalgia of really good rock music from the eighties that still hangs over a lot of Maine, but the word also spoke to the landslide of change that Maine faces: climate change, the collapse of commercial fishing, the gentrification of its working waterfronts, and a truly vast chasm between the monied Maine and the working Maine that has been in fishing and in the paper mills and in harvesting lumber here for centuries. The novel is a love story, and in that sense it echoes Fleetwood Mac’s “Landslide” in every way: the characters in the book see their love “taken down,” to quote Stevie Nicks, and we watch to see what will happen to them next. But the novel also explores the larger landslide going on here in Maine and almost everywhere else in the United States. How will we weather the changes? Will we? Who will we become as a place and as a community of people? What and who do we want to become?

LN: We love the image of teenage boys as wolves. When did that image come to you? What do you think is unique about mothering teenage boys that you wanted to explore in this novel?

SC: The boys in Landslide were wolves from the very start. From the first words that they speak in the book, they were the older wolf and the younger wolf. I think calling them wolves was a fun way for me to unpack some of the stereotypes of boys and interrogate them. I have two of this species, and on good days I like to think that I speak “teenage boy.” I’ve known dozens and dozens of them. They run in packs. They wrestle and nip and call each other out, and then reward each other with abiding affection and love. I believe that boys are so often misread and misunderstood and sold out in our culture. Wolves are a smart animal. Capable and beautiful and wily and strong. Wolves are also slightly dangerous and unpredictable. And above all else, wolves are wild and, in my experience, incredibly big-hearted to their pack.

I think the singular experience for many mothers of teenage boys is how they don’t “know” boys intrinsically when the boys are born, and they worry that the boys will be “wild” and that they won’t understand boys. They have to “learn” boys. So the boys are other—the boys are wolves, but they are also so very known to the mothers and so very loved. The bond between mother and son is often a deep one and pretty intractable. It’s also often a hard-earned bond. The mother and son have had to learn to really understand one another as the boy has grown into himself and begun to separate. The boys in Landslide test their mother. And they never lose their ability to put her back on her heels. They adore her. They are devoted to her. But they press her. And in this way they never stop being wolf-like in their ability to beguile and surprise.

LN: Jill, Kit, and the boys clearly love each other, but they are often putting up walls around themselves, unable to see or understand each other—or feel seen or understood by each other. What questions about family life and individuality were you exploring when you began the novel, and how did those questions change as you wrote?

SC: Questions around the idea of coming-of-age. Of what that really means to boys. Also questions around what it means to experience first love. First sex. First experience with drugs, and how much of that is going to be private and experienced individually and how much, if any, will be shared with a parent and should it be. Questions of separation. Of the need for teenage boys especially to begin the arc of separation and individuation from the mother. Some say that the mother is the boy’s first love, and so the leave-taking can feel that much harder and fraught, and yet crucial.

Questions of identity in middle-age. What happens when we doubt ourselves to our core, because the thing we most love to do in the world isn’t available to us anymore? Can we change? Is change possible? Can we dare ask for help? Why is it that when we most need help we don’t ask for it?

The questions I was asking around the boys in this book stayed fairly constant. The boys' refrain was essentially: I need you Mom, and now please go away and give me space until I ask for you! The questions I was asking around marriage changed. The novels wonders if a marriage can survive great tumult and personal crisis. What happened for me in the writing of the book is that I saw how much more vulnerable we can be when we are really taken low, and how much we can try to hide our suffering and our fear. When my characters crack near the end of the novel—when their guard comes tumbling down—it was in some ways as much a surprise to me as to the people who love them in the book. I was moved to tears at points in the writing, and this is probably why I write: to learn as I go and to write into these questions and see what answers rise to the top.

LN: There’s a lot of pain in the novel, but there’s a lot of humor, too, particularly in the dialogue between the boys and between Jill and the boys. Does writing humorously come easily to you?

SC: It's a great pleasure to entertain the idea that humor comes naturally to me on the page. I can only hope so. From the very start my vision for this book was one infused with humor. With the deadpan and lancing blows of teenage-boy language. There's such comic timing between boys and such understatement and nuance and fantastic subtext. So much is implied in boyspeak. So much is meant to be understood implicitly and withheld. Jill, the mother in Landslide, has grown pretty good at intuiting and inferring the boycode, but she’s always hustling to learn more, and this provided me with all kinds of good comic set-ups. The humorous is its own love language. And Jill really needed a way to show the love without naming the love, and to show that she was there, unflinchingly, with unconditional love, so she resorted to humor.

LN: In Landslide, Kit is a fisherman who has seen his industry change over the years and is worried that his profession may not be sustainable. How has living in Maine and your understanding of the economic forces in Maine shaped this novel?

SC: In a word, entirely. I’m fourth-generation Maine. I grew up in the part of the state that I write about, and in this way Landslide is a love letter to coastal Maine and also a sad love song. The novel really asks what Maine wants to be next. There is still time to save commercial fishing in Maine—and in doing so, to save this iconic Maine “brand.” There is still time to keep the waterfronts in Maine “working” waterfronts where fishermen have access. But the time is nigh. My hope is that the novel captures some of this urgency through the granular stories of Kit and Jill and their two wolves.

LN: Your novel has a strong sense of place with beautiful descriptions of the ocean. Are there any particular writers whose work has influenced you in regard to writing about place?

SC: Hmmmmm. Where do I start? I actually grew up on poetry. I'm someone who did all my undergraduate and graduate work in poetry, so language and imagery and what I like to call "lyrical bursts" are elemental to my work. I don’t feel I'm writing well if I’m not really “seeing” and “doing language” on the page, to quote the inestimable Toni Morrison. I feel it’s our duty and honor as writers to “do” language and to render place, and in this case the ocean, in all its different lights and moods.

When I think of writers who do language and place well, I go to the poets first: Claudia Rankine, Louise Glück, Carolyn Forché, Toi Derricotte, and Sandra Cisneros, and then onwards back to Pablo Neruda and Basho and on and on. Then I go to prose writers like Virginia Woolf, Tove Jansson, Ian McEwan, Toni Morrison, Maggie Nelson, Bryan Washington, and where do I stop. I think the most exciting experience as a reader is to stumble upon language that's trying to say it “new,” and in doing so stops us in our tracks and changes our sense of meaning about the world we’re living in.

LN: Which books are you looking forward to reading in the coming year?

SC: My stacks are high right now! And here in January, I'm still catching up to last year. I'm very much enjoying Homeland Elegies and am about to start Luster. I thought that The Dragon, The Giant, The Women had moments of such transcendent language and extraordinary tension and pace. Meanwhile, I am also reading Claudia Rankine’s Just Us—I read it slowly to savor its distillations and profound insights. I recently finished Bryan Washington’s Memorial, and it’s hard to find someone writing better on food and place and the limits of love language. Real Life by Brandon Taylor and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste are next. Stacks of such riches!

Susan Conley is the author of five critically-acclaimed books, including her new novel Landslide. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Paris Review, The Virginia Quarterly Review, The Harvard Review, and others. She’s been awarded multiple fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, as well as fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writers' Conference, The Maine Arts Commission, and the Massachusetts Arts Council. She’s on the faculty of the Stonecoast MFA Program and is co-founder of the Telling Room, a creative writing lab for kids in Portland, Maine.