What Is Otherwise Infinite, the new collection from Vermont poet Bianca Stone, deftly weaves between the physical and the metaphysical, the daily domestic trials of life and the larger trials of being human in this world, this universe. The book, which is released by Tin House on January 18, 2022, is described by poet Dorothea Lasky as “a majestic exploration in what it means to be alive....there is language here—real poetry—that transforms your way of seeing the world with its terrifyingly beautiful presence. This is a legendary book. It will change you. You must read it.”

As a poet who also knows her way around real, transformative poetry, Kristin Maffei seemed the ideal person to interview Bianca for Literary North. Thank you, Bianca and Kristin, for this excellent interview, and congratulations on this incredible new book, Bianca!

In celebration of her book's launch, Bianca is in conversation with Dorothea Lasky on January 18 at 8:00 pm. This virtual event is sponsored by The Vermont Bookshop.

Bianca Stone was a few years ahead of me at NYU, and was already a bit of a legend when I arrived right before she collaborated with Anne Carson on Antigonick, an illuminated book of Carson’s translation of Antigone. Her work speaks to me on a deep, nearly instinctual, level, and leaves me thinking of her images long after I’ve finished a given poem. I was so excited when Rebecca and Shari offered me the opportunity to interview her.

Stone’s latest book, What Is Otherwise Infinite, is out today from Tin House. It was listed as a Most Anticipated Book of 2022 by The Rumpus and it wanders, with the reader, through the world’s great questions as we all seek to find connection and a place.

Kristin Maffei: What Is Otherwise Infinite feels to me ambitious and encompassing, an exploration of the duality of human/nature that feels both intimate and universal. How did it come to be? Why is now the right time to delve into such a complex topic?

Bianca Stone: The poems really started coming together as a book from a sudden interest in duality—brought on by a real struggle with my own mind, a feeling of being very much unable to connect—a depression, certainly—as we all experience, especially in the pandemic—but also a lifetime of desiring to transform out of a seemingly very limited state of being. That state includes—or maybe is—depression, but that’s such an unsatisfactory word. In any case, I got excited in the idea of the “two hands of God,” and the inner unity of opposites, such as Alan Watts writes about. I was suffering and desired revelation. Real revelation. There was also a kind of unavoidable anxiety about nature, and a feeling of wanting so much to be in nature, and feeling I was so far from it. Or didn’t deserve it, or belong with the world. I think poets are writers who focus uniquely on this perceived divide between Man and Nature—like the Romantics who first started really seeing consciousness interacting between the two in the poems, I think that’s now somewhat traditional in poetry. But why do I feel I do not belong here? It’s odd. This feeling of being alien was not a product of a natural order, but of idea—this led me to a lot of investigations towards a kind of mysticism, a kind of unknowability of our place—it can be exciting, or it can be devastating—but also I developed a focus on language and a kind of self-analysis. Indeed, language is really at the heart of this; it is our unique situation as a species, although it is fumbling, flawed, always inadequate—but how hard I’ll try to be precise! As close as we can get is enough! It is our special song among the animals.

Why is this the right time? Climate change haunts us not-so-subtly. It isn’t possible to not bring this into contemporary writing. It touches everything. And look what danger comes from feeling we are not of nature, that it is optional to care—meanwhile, it is us. This is a self-destructiveness on the part of humanity, a masochism. And that is exactly what we do on private scales, to ourselves. I wanted to stop this, or at least to acknowledge it in myself. Why do I do this to myself? Why do I long to stop but keep reinforcing it? And what beauty is there in the meantime between people and the world?

KM: There are so many incredible images in this book, but one that especially seems to be a microcosm of the whole book is this stanza from “Illuminations:”

Sometimes you pass a house in Vermont long abandoned

and sinking into the ground,

and there will be, every spring, daffodils

within the mass of weeds and new forest,

where someone once cultivated and controlled nature,

developed flower beds into specific patterns,

come back like bright, natural scars.

You are a visual artist as well as a poet, though there are no illustrations in this collection. How do you know when an idea is or needs a visual component, and when you'll be able to capture it in words?

BS: That poem is a homage to illuminated manuscripts, old religious Book of Hours books, that combine text and image so magnificently. These were the first books! And what incredible items they were—they had no gulf between “Illustrated” and “just-text.” Text was illustration. And not only that, but the livingness of the book themselves: made from the guts of animals, intricately mixed inks from natural objects, such potions, varieties of natural sources all assemble these books—these books—are a great metaphor for human trajectory. The poem itself is a nod to the creation of my book of poetry: the idea that more than one person “created” it, that it’s filled with references to other texts and myths; that mistakes are always made, liberties taken, things unfinished; that allusions from the past will crop up like a long-ago cultivated plant, now somewhere between wild and domesticated.

When I was deeper into my poetry comics, I struggled more with the decision to either focus on the poems, or poetry comics—although even then, it wasn’t much of a struggle. I use my more fragmented, unfinished poems—or poems that failed, I’ll use their one good line for a poetry comic. But for me, I know intuitively when something demands language or image. Using both is more experimental, each time is very different. I think what I’ve become interested in is how there’s a certain type of symbolism conveyed in images that can’t be expressed in the same way with language—good poetry inherently understands this, as it does not rely on logically descriptive language. But even so, images can do a lot of unconscious work simply by being before you, letting you interact with them without any informative words at all.

KM: The poems “Routine” and “The Malady” both dance with the concept of productivity, and ergo with mortality, in a distracted world. How do you write, facing that down? Is this an appropriate time to ask, “what’s your process?”

BS: Yes, those poems play with the bombardment of our habit-forming wellness industry that is so seductive to a distracted culture—and especially for me as a person who grew up without any of that structure. I craved discipline for many years and chased it erroneously, since it was entirely the wrong focus for my attention, and, again, became a formation of pain. But we all suffer from a kind of, as Rilke put it perfectly, desire to “change your life.” Meanwhile, life flies by and you’re not living it…but process, yes. What is my process? Speaking of discipline, one thing I did realize is that you can’t sit around waiting to “feel” like writing—for many of us, we don’t feel like doing anything. Interestingly, I’ve found my process involves a process of getting into the mode of writing; creating a poetic state. I do that though, of course, reading poetry. I have my favorites that inspire me, Franz Wright, Rilke, my grandmother, miscellaneous new books I get in the mail—my friends. I write and read every day, but that doesn’t mean I write a “new poem.” Sometimes it’s just notes, ideas, thoughts. When I’m working on a book, it’s like I’m in an editing state. And in the editing state, I am always also in my most vivid writing state. Deeply editing my poem inspires me to write new poems.

KM: You run the Ruth Stone House and several of your poems reference specific places, many in Vermont. How do space and place play out in your work?

BS: It is interesting to think about how space time works in poetry, and certainly, while one sits at their desk and writes a poem, often times the poem reflects back onto that present moment—and yet even in that moment of reflecting on it, it becomes not the place you are in anymore, but an event in the poem. Often we are struck by something we’re seeing in real-time and feel compelled to write a poem about it, like the really amazing bird in the bush right outside the window, or the mountains, their beauty, as we are in relation to it, affects us and we create something out of it. When I was in NYC I wrote of that landscape a lot in a similar way. But there is too, of course, the event of memory, and capturing it, nostalgia and hauntings: those landscapes we want to rip from obscurity and bring into the moment. Sometimes it’s even easier to write about a place we’re no longer in. But what is this new place in our poems? It’s some liminal space for the speaker-self and the reader-self to explore together, to play, in seriousness, with their realities. There is too the desire to connect with our surroundings, and though I am not laying in the field, but looking at it, or thinking of looking at it, I desire to lay in the field, and that desire demands its place in the poem. We want to place ourselves in the world, to be real, and a poem is like a version of knowing ourselves to be in existence. Even in such a ghostly state, there feels a kind of immortality.

KM: What's the best thing you've read recently?

BS: I was up late into the night slowly reading Martin Buber’s I and Thou, and I see that it’s one of the most important books for me to read right now in my goddamn journey. The simplicity! And yet, how much I resist understanding it: it is one you must slow down to appreciate. I keep wanting to skip ahead—really I don’t even know why skipping ahead seems more real that reading what is in front of you—but I keep catching myself, and instead of skipping I read the most incredible lines. (It’s so interesting that those moments I desire to skip turn out to be moments that are the most resonant with me.) His work is entirely about the relational, which is everything in poetry. “Inscrutably involved, we live in the currents of universal reciprocity.” I mean—that is the wave poetry finds itself racing upon.

KM: What’s next for you?

BS: I have become obsessed with this idea of the relational in poetry, and that’s also a crucial element in the psychoanalytic dyad—those two occupations are my entire appetite as of late, and I can’t seem to stop reading and thinking about it. I am determined to write a collection of lyrical essays, or vignettes or lectures or something about it all. Our human desire to be known, and absorbed, and our desire to know and absorb others. We’re all very involved: in Other and in World, and we want to heal-up, want to grow as a species; how can we do this with more curiosity? More nuance? Our world needs radical change, and I believe we must start with the relational. Poems, of course, always begin with me. But I am deeply interested in this dynamic relationship via language, that speak to greater ideas of human consciousness.

Photos by Bianca that reflect her work on What Is Otherwise Infinite.

Is it the fog lifting or the tree rising… who cares?

Titles

My desk

Bianca and Odette’s ink hands

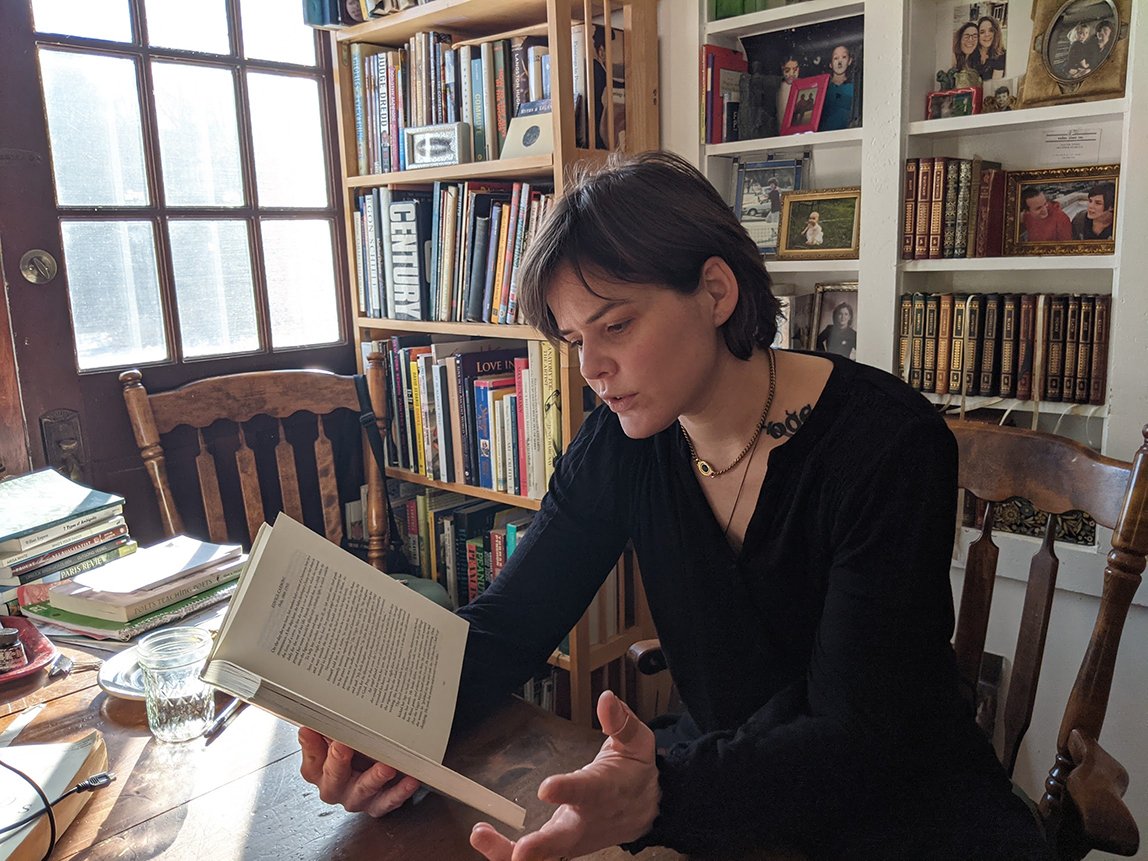

Bianca Stone is a writer and visual artist. She was born and raised in Vermont and moved to New York City where she received her MFA from NYU in 2009. She is the author of Someone Else’s Wedding Vows (Tin House, 2014); Poetry Comics From the Book of Hours, (Pleiades, 2016); The Mobius Strip Club of Grief (Tin House, 2018); and the children’s book A Little Called Pauline, with text by Gertrude Stein. She collaborated with Anne Carson on the illuminated Antigonick, a book of Carson’s translation of Antigone (New Directions, 2012). Her poems, poetry comics, and nonfiction have appeared in a variety of magazines including The New Yorker, Poetry Magazine, American Poetry Review, and many others. She has returned to Vermont with her husband and collaborator, the poet Ben Pease, where she is director of programs for The Ruth Stone House, a literary nonprofit artist residency, letterpress studio, and community poetry center.