We feel so lucky to live in the Upper Valley, an area of Vermont and New Hampshire that is home to so many wonderful writers. One of these is Cleopatra Mathis, founder of the creative writing program at Dartmouth College, where we’ve attended many a reading in the Cleopatra Mathis Poetry & Prose Series over the past several years.

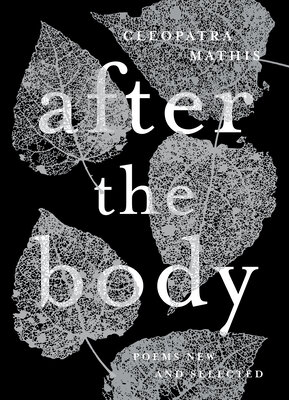

Mathis’ latest book, After the Body, is a collection of new and selected poems released by Sarabande Books in July 2020. This stunningly beautiful collection begins with Mathis’ new poems, which address aging, illness, and the limitations of the body. This remarkable collection draws its selections from seven previous volumes, with poems about marriage, family, and the natural world. It is a book that made us wonder at the human anatomy, and think and feel deeply; it is a book we know we will return to again and again.

We were delighted and honored that Cleopatra agreed to an interview with us. We hope you enjoy the interview and are able to hear her read from this deeply moving, beautiful book.

Again, some new curiosity turns me

this way and that. If I leave for a few minutes,

the world changes, resisting my hold on time;

it is a planet after all , with its own moon

and the night's business to do. I catch myself

wondering how to say goodbye.

—Cleopatra Mathis, from “Being Apart”

Mathis will give a virtual reading with fellow professor and poet, Joshua Bennett, at Dartmouth College on Thursday, April 1, from 4:30 to 6:30 pm.

Literary North: How did this book come about? Did you feel ready to put together a collection of selected works, or was this a project suggested to you by someone else? How did it feel to revisit your earlier work in the context of a collection?

Cleopatra Mathis: Initially, I’d asked Sarabande [Books] if they would be interested in reprinting What to Tip the Boatman?, which had been out of print for several years. They thought it would be better to do a new and selected instead. Deciding which poems to include from my seven previous books was a lot harder and more surprising than I expected. I found myself in the presence of a younger self, one who was in some ways more imaginative and inventive, but sometimes less proficient in the craft. And if I loved the poem enough to try to revise it, I found I could not re-enter the mental space that inspired the poem. Finally, I had to accept that the more flawed poems had to stand as they were or be left out. I am still not sure if I chose correctly. There are other poems that I didn’t include because they did not work with the book thematically.

LN: As the title of After the Body foreshadows, this book is often concerned with bodies: your own, your children’s, missing bodies, and failing bodies. Did you see this as a driving theme for organizing this book, or did that theme arise naturally out of your preoccupations in many of the poems?

CM: Yes, my preoccupation with bodies was how I chose to approach the book; I’ve always been aware of that focus in my work, though the subjects and their treatment have changed. I began as an elegiac poet, in some ways romanticizing those who I’d lost, but I think I grew into a writer who is fiercely focused on the impermanence of all bodies. In putting the book together, I tended to ignore the poems that didn’t in some way use the body as an evolving source of study or conflict. In my recent work, I have wanted to blur the distinction between individual bodies. In my own personal struggle, I focus on the relationship between spirit and body, knowing that over time the body is diminished, the spirit augmented. My physical self is much more limited than it once was and therefore less compelling. Instead, I am drawn to the result of losing my power over my body.

LN: After the Body covers a period of time in your writing life from 1979 to the present. What do you find to be the main difference in the way you approach poems now? In what ways, large and small, has your creative life changed over the years?

CM: I am not very faithful to the practice of writing, meaning my process has never been a reliable one. It is hard for me to put writing before everything else—previously parenting and teaching and now cooking and housekeeping and reading. I’ve never had time to read as much as I’d like, and now I do. While reading can put you in a receptive place for poetry, it also can eat up the time for writing. As an older writer I find that I am less hungry for recognition and praise. I’m also less content with my work: I don’t want to say the expected thing or to repeat myself. As a young writer, I found that the poems came faster and easier: my subjects were new to me. I still have the same urgency to write, but the crafting of the poem has to be meticulous. I am a slower writer than I was because I question my usual tropes and approaches, measuring myself against what I’ve already done. I struggle with trying to find new forms for what I have to say. I’ve never been a writer who rushes to publish in journals; the poems have to be with me a long time and go through many drafts before I’m ready to let them go. When I was younger, the publication process was more important because feed-back from the world was more important. It’s a relief, really, not to think about that approval.

LN: Many of the new poems in this collection are written with a deep curiosity about the body’s mysterious beauty but also its failings due to age or illness. How do you feel these poems differ from your earlier work about the body?

CM: The body’s failures are overwhelming to me, and as I wrestle with the subject I find very little solace. I find it sad that as we grow into wisdom and clarity, as many of us do, we also lose control over our physical selves. I suppose most of us don’t consider the possibility of the body’s failure. I tend to treat my body as something to be conquered or overcome, and the new poems reflect that struggle and sense of otherness. My body has become a foreign thing, something I relied on for years without questioning its strength or permanence.

In my earlier work, the bodies I wrote about exclusively belonged to people who I cared for. I wanted to honor the people I cared for—the work of elegy. As a mother, my children’s bodies had to be protected above all else; their possible loss was terrifying to me. The loss of my brother when he was 26 was initially the loss of a sibling, but as I have gotten older the significance of his death has evolved. I identify more with my mother’s tragedy of senselessly losing a son that young. I am more interested in what we have to do to survive—the resiliency and will that it takes.

LN: Some of your very earliest writing is grounded in the landscape of Louisiana, where you grew up. In 1981 you moved to New England. What was it like to begin writing from such a new and different landscape, a place with a real winter? What is your relationship now to the Southern landscape? Do you find it easier or more difficult to write about a place from a distance?

CM: My childhood in Louisiana is ingrained in me. The place itself still features in my dream life, and lately I've been returning to it even more in my writing. There is a sense of the subject not being finished, that there are still things that perplex and weigh on me. I fell in love with the northern beach on Cape Cod when I was a fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in 1981-82, my first time in New England. The ocean was a kind of love affair for many years. It thrilled me, absolutely, and fed me. Creatively, I felt that I’d found a home there, that it would provide me with everything I needed to say. I still find the snow inspirational.

In many ways it is more difficult to write about Louisiana now. In the beginning it was the source of a personal mythology; as I created a mature self in my twenties, I used it as a way to approach metaphor. It was so much a part of my process that Stanley Plumly, one of my MFA professors at Columbia, warned that I might not have anything to write about when I exhausted that subject. My mentor, Stanley Kunitz, on the other hand, saw my obsession as integral to developing my voice. The natural world I grew up in was a lens through which I could manage my childhood’s difficult emotional material. The body of that landscape fed me because I always felt foreign to the culture; the tension that the place inspires in me was what drove the poems into being. As I write new poems now, I am using my autobiography more and the actual landscape less. I speak more directly.

LN: What is your writing process like? Has the pandemic changed your process or your writing rhythm?

CM: I write on many scraps of paper, often on post-its—just lines or images that come to me. I collect them and at some point, when I have time to sit down with a collection of them a poem emerges. This is so haphazard that I am reluctant to call it a process! I used to be a faithful and organized keeper of journals, but one of the ravages of Parkinson’s is that I no longer can read my handwriting, and the act of writing itself is unwieldy and even painful. In the effort of trying to control my hand, I end up forgetting what I meant to write down. I can’t get lost in that reverie my free hand used to allow. It’s very frustrating, so I am trying to learn to write poems on the computer-—something I always warned my students against! I have found the pandemic terribly distracting, as well as the political climate of the past year. It’s been harder to focus on imaginative work and even my reading mostly has been limited to often-sobering non-fiction having to do with real events and the history that has brought us to this place in time. I am truly impressed with the poets among us who take on this work.

Cleopatra Mathis was born and raised in Ruston, Louisiana, and has lived in New England since 1981. She is the author of eight books of poems; the most recent is After the Body: Poems New and Selected, published by Sarabande Books in 2020. What to Tip the Boatman? (2001) won the Jane Kenyon Award, and White Sea (2005) was the recipient of the New England Poetry Award. Other prizes include a Guggenheim Fellowship, two fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, and two Pushcart Prizes. Her poems have appeared widely in journals, magazines, and anthologies, including The New Yorker, Threepenny Review, The Georgia Review, The Southern Review, Ploughshares, Best American Poetry, and The Extraordinary Tide: Poetry by American Women. The founder of the creative writing program at Dartmouth College in 1982, she lives with her family in East Thetford, Vermont.