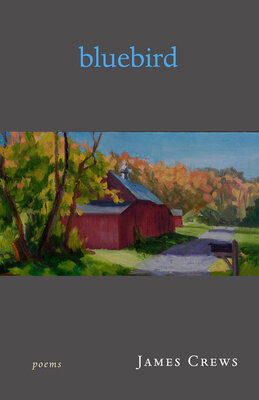

James Crews is a wonderful poet and a kind soul. We feel so lucky that he joined us for the very first Poetry & Pie and even more fortunate that he shared an advanced copy of Bluebird (out now from Green Writers Press) with us.

If you need a book to quiet your mind and wake you up to the beauty of the world all around you, look no further. Bluebird is a beautiful book filled with poems on silence, kindness, neighbors, rural life, nature, and relationships, and it’s the perfect companion for our current times. Thank you, James, for taking the time to talk to us about Bluebird!

p.s. We recently hosted a writing workshop with James and are delighted to be partnering with him to present his latest workshop: Radical Gratitude and Embodied Writing. This six-week long workshop begins on August 22. Space is limited and there are just a couple spots left. For more details and to register, please visit the workshop page. (Workshop has filled! Thanks for your interest.)

Literary North: Could you talk about the process of organizing the poems in Bluebird and how you chose to divide the book into three sections?

James Crews: I love organizing poems into a book form—it's one of my favorite parts of the process—and I spend a lot of time and attention ensuring that each poem flows into the next. Besides the individual drafts that the poems went through, I probably assembled and re-assembled this book at least ten times to get it just right. This is tough to explain, since it's mostly an intuitive process, but I do my best to listen to the poems, feel how they're talking to one another, and then look for larger pauses within the manuscript to divide the book into several parts. I also work as a creative coach, helping others put together their books, and it’s the most fun I have working one-on-one with folks.

LN: Part One of Bluebird begins with a quote from Maimonides: “We are like someone in a very dark night over whom lightning flashes again and again.” What do these words mean to you and why did you choose to use this quote to start off your collection?

JC: There are a lot of different threads going in Bluebird, but one of the main threads for me is the practice of mindfulness—and here, I almost wrote “the struggle of mindfulness.” I wrote most of the poems in this book after I had just taken a leap and moved to Vermont to be with my now-husband. I didn't have a regular job at first, so I took that opportunity to try and deepen my meditation and mindfulness practice. Since I see my writing as part of my spirituality, of course the concerns seeped into the poems as well. The Maimonides quote appealed to me because I think we put far too much pressure on ourselves both as creatives and as spiritual practitioners. We seem to think the point is to reach this place of unbroken presence and equanimity in the writing and/or the spiritual practice, but that seeking of perfection rubs against our flawed human nature. So I feel that all I (and we) can ever really hope for are “flashes" of insight and understanding, fleeting moments of presence when we're able to touch into the deeper world around us and within us. On a practical level, I also felt that epigraph fit perfectly with the first poem in the collection, “Fireflies," which says essentially the same thing. Some insights come like lightning . . . while others arrive as firefly flashes. In our lives, there are mostly these smaller revelations or flashes, and though we might be tempted to look past them, they can add up to a life lived fully, if we've been paying enough attention to them.

LN: Your poems “Night-Dweller” and “Adoration” both begin with quotes by Mary Oliver. Many of the poems in Bluebird bring her work to mind. How has Mary Oliver’s work inspired you and your writing?

JC: Not long after I first moved to Vermont, I was drawn to Mary Oliver's work, and would check out book after book by her from the Bennington College library. I know that a lot of Vermont writers feel the influence of Frost, but Oliver has been a far larger influence on my work. I would read her poems in the morning, then go out for long walks and encounter some of the plants and animals with which she was communing in her own work, so I began to feel this close kinship with her. I wasn't surprised to learn that she taught at Bennington College for a while (just about ten minutes from where we live in Shaftsbury), and lived on-campus there. Though some might think her poems too easy or accessible, I think that her welcoming and open-armed embrace of her connection to the natural world serves as an example for all of us poets. I once heard Mark Doty say at a reading that although he loves Oliver's poems, his one complaint is that she only includes the more positive aspects of nature, seldom discussing the presence of trash trucks, or the roar of a jet passing overhead, for instance. That's never bothered me. I see her poems as aspirational in a way, urging us to go outside, and pay kind, loving attention to whatever world is around us.

LN: We couldn’t help but notice the repeated appearance of the word “claim” in several of your poems (for example in “Living Light,” “Claim,” and “Spotted Wing Drosophila”). Though the poem “Orb Weaver” doesn’t explicitly use the word, we can sense it below the surface. Can you speak about how you were playing with many facets of the word such as claiming time, claiming joy, and staking a claim?

JC: The recurrence of the word, “claim," was completely accidental, so I appreciate you all pointing it out to me! It does seem important because anytime we enter a new life (relocating, getting married, starting a new job), we have to claim more and more of who we are. That's part of the self-discovery process that happens as we grow. I've struggled over the years too with “claiming" my identity as a poet, believing that my voice had anything worthwhile to add to the larger conversation. I often hesitated to share poems for fear people would think I was bragging or simply “self-promoting,” but as I got in touch with my own intentions for writing poetry (to connect more deeply to myself and the world around me), I grew less fearful of sharing them.

“Claim” is a central poem in the collection too, in that I'm urging myself and others at the same time to find joy even in the plainer moments of life, even in the experiences we'd rather not welcome, like checking ourselves for ticks. What a pleasurable experience that could be if we didn't allow the labels or annoyance to get in the way—not that I always succeed. Yet it's an essential part of living the fullest life possible, embracing the so-called positive and negative aspects all at the same time. Especially during these uncertain times, if I can both name and claim my fear and anxiety, it comes out of hiding and has less power over me.

LN: Your last book was Healing the Divide: Poems for Kindness and Connection. These themes of kindness and connection continue in Bluebird, most strikingly in the poems “Neighbors” and “Kindness.” The poem “Neighbors” feels particularly apt at this moment when there is an obvious need to help and protect each other. Yet there is a need to be separate as an act of kindness, in order to protect each other. Would you share your thoughts about the forms that neighborliness and kindness can take and how kindness “keeps us alive”? When was the last time an act of kindness moved you?

JC: Since editing Healing the Divide, and leading quite a few workshops around that book, I've grown attuned to the presence of the many kindnesses in my life: notes from readers about poems I've written, my mom-in-law handing us a jar of pasta sauce she made, a good friend offering me the use of her office as a quiet space while she's out of town. One of my neighbors recently left a note (on a blue notecard!) about Bluebird on our screened porch. Because of distancing, I had left a copy of the book in her mailbox, and so we had this wonderful exchange about the book that culminated in a little chat in her front yard. I was so moved that she took the trouble to drive all the way to my house and leave the kind note.

I also agree that a poem like “Neighbors" feels very apt right now because I do believe that so-called “small kindnesses" keep us healthy and connected with each other. Many of us are having to be more creative about how we facilitate and find our connections, and how we might help other people in need, but it takes so little to brighten someone's day. Someone told me about finding painted rocks that a neighbor's child leaves outside his door, which moved him to tears because of how much he misses his children. Stories like these are all around us now, and they can be a balm in the face of such negative news.

LN: What is your relationship to silence, as a human and as a writer? Do you have recommendations on ways to encourage more silence in our own lives?

JC: I seem to need a certain amount of silence in my life in order to thrive as a writer, and as a human being. I've always loved working in silence best, and will often wear earplugs just to inhabit a deeper silence and stillness while I'm working or reading. I do think there are some practical ways to invite more silence into our lives. Unless I need the ringer on, I turn off all sounds on my phone, and I won't let my computer announce new messages, emails, or notifications. On the days that I can, I also try to preserve a certain amount of mental silence each morning by meditating with my husband as soon as we wake up and waiting for hours before checking my phone or diving into email. I also try not to read emails/messages or use the internet past 8:00 pm each night. That time is also reserved for meditation and/or reading in order to let the noise of the day (and my busy mind) fall away. It can take a lot of discipline to keep all this up, and I fail plenty, yet I notice that when I'm able to leave these gaps and spaces, I'm just so much calmer and happier, even during this pandemic. Though I'm a former news junkie, I've also had to limit how much news (very little for me) I'm willing to take in each day, and certainly not in the morning when the mind is still fresh and free.

LN: We were struck by the final lines of “Milkweed”: “just when we start to believe / you can’t possibly be that delicate / and still survive in this world.” That the world is full of intricate delicacy is a wonder given how harsh the conditions sometimes are. Can you talk about ways we can be delicate in a world that doesn’t always value that quality?

JC: Our heads don't value delicacy and gentleness, yet our hearts crave it. I think that noticing when we're inhabiting that harsh space —being hard on ourselves as well as the people in our lives—can keep us in touch with the delicacy I talk about in “Milkweed." Certainly, many of us are finding refuge in the natural world, with its promise that —in spite of the immense shifts caused by climate change—it can still provide us with a respite from the daily uncertainties. I think I was also talking about myself in those lines, at least on days when I feel so delicate and breakable that the wrong word or a single news story can send me spinning off into a rabbit-hole of worry and fear. Yet the more we honor who we are with gentleness and acceptance, the more we build resilience.

LN: Which books are bringing you comfort right now (old friends or new discoveries)?

JC: Writers and Lovers by Lily King is a wonderful, recently published novel; Bonfire Opera by Danusha Lameris and Indigo by Ellen Bass are two collections of poetry I can't live without right now. I also thought that Where the Crawdads Sing by Delia Owens was a great novel and engaging story, as well as an invitation into a closer and more delicate relationship with the natural world. It kept reminding me to step outside, walk through the farm fields around our house, and allow myself just to be with all the bittersweet vines and goldenrod and Queen Anne's lace still insistently growing.

James Crews’ work has appeared in Ploughshares, Raleigh Review, Crab Orchard Review and The New Republic, as well as on Ted Kooser’s American Life in Poetry newspaper column, and he is a regular contributor to The London Times Literary Supplement. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and a PhD in Writing & Literature from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. The author of two collections of poetry, The Book of What Stays (Prairie Schooner Prize and Foreword Book of the Year Citation, 2011) and Telling My Father (Cowles Prize, 2017), Crews is also co-editor of several anthologies of poetry, including Healing the Divide: Poems of Kinship and Connection. He leads Mindfulness & Writing workshops and retreats throughout the country and works as a writing coach with groups and individuals. He lives with his husband, Brad Peacock, in Shaftsbury, Vermont.