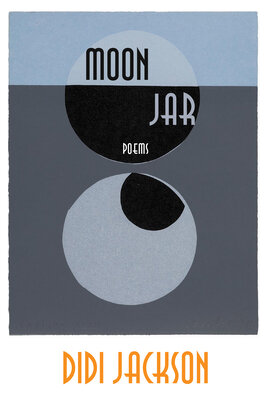

Didi Jackson is a terrific poet. She writes accessible poems that are packed with startling imagery, art, precise language, and delicate emotions. She manages to make the shocking and heart-breaking very real and yet very tender at once. Though her new book, Moon Jar (Red Hen Press, 2020), opens with the incomprehensible grief and practical horrors of her husband’s suicide, the journey through this beautiful book takes us into hope and a future where love and healing are possible.

We were fortunate to have Didi read at Poetry & Pie in 2018, where she introduced us to some of the poems that eventually made their way into Moon Jar. Since then, we’ve gotten to know Didi more and have seen her kindness and talent expressed in so many ways. We are grateful for her friendship and delighted to introduce you to her breathtaking book. Congratulations on this book, Didi, and thank you for spending some time with us!

This is not a poem of coming spring.

This is a poem well aware

that gray flesh is dead flesh.

All of the ripe listening

comes at a cost. The first

sky is in all skies.

The first song

is in all songs.

—from “Listen” by Didi Jackson

Literary North: Many of the poems in Moon Jar, particularly in the first section (“Your Husband was a City in a Country of Sorrow”), are suffused with your intense grief. In fact, you share a quote from Toi Derricotte at the opening of this section,“...I cannot help but feel responsible for your discomfort. So as you read, you will feel me tugging it from your hands.” Would you mind sharing how it felt to write these poems, and how it feels to share them with others beyond your family?

Didi Jackson: At first, writing the poems was a sort of therapy, an attempt to make sense of something that in my particular case hit me from out of nowhere. But eventually, I became worried about these poems being out in the world. After a poetry reading in New York City, I was talking with a friend who is a nurse about how concerned I was in passing my pain on to those listening in the audience. The reality I wrote about was so horrible and tragic, I felt responsible for transmitting such suffering. She helped me think differently about my work by pointing out how desperately she needed to hear my poems. A friend of hers just lost a husband to suicide, and she felt that my book (if it had been a book at that time) would and could help her immensely. That was long before my poems about suicide had become a manuscript, but, in that moment, I was sure that I was doing something good out of something cataclysmic.

The day my book was published, I cried. As comments came rolling in on social media, I realized the extent to which people would now know the details, the deep darkness of suicide. For some reason, I want to protect everyone from what I went through. But I guess it is impossible to protect those we care about from the inevitability of some sort of suffering in life. I can only hope that my book eases my reader’s pain and gives some hope in the end.

LN: The book begins with a poem called “Signs for the Living,” which has a very uplifting ending, a sense of flying, certainly of hope. How did you decide to open the book with this poem?

DJ: I feel like the poem “Signs for the Living” sets the theme of the book. In a way, it gives the reader a preview of what is coming: the swirling questions and difficulty of surviving suicide loss in the first section, then a movement to a new life and a new way of being in the second and third sections. I was able to regain a foothold of hope in my life, and I want my book to reflect that. Those yellow braids behind the speaker in the poem represent that hope.

LN: Your poem “A Poem in Reverse” is astonishingly lovely and moving. Did the idea of writing the events backwards—as an undoing—occur to you as an idea before you began to write it?

DJ: Thank you so much. I came across a poem by Victor Hernandez Cruz called “El Poema de lo Reverso” not long after my husband had taken his life. Of course, so many nights I imagined what it would be like if I could turn back time and maybe save him. Many of the poems I was writing at the time were about what happened after the suicide, so I thought it might be interesting to imagine what if it had never happened. I borrow some of the same language as Cruz: backwards, seed, shrink, Atlantic, years, wood, time. But I use them like scrabble pieces, put them in a bag and shake them up, then pull them out one by one and place them within my own lexicon of imagines concerning death, the hotel room, the body found, Florida, and so on.

LN: We love noticing the words and phrases that reappear in a writer’s work. In yours, we noticed “jar” (of course), “moon,” “snow,” “white,” “and “moth.” And winter appears over and over, as a thing/season you have fallen in love with (“Everyone Says I Should Write a Love Poem”) and what you have become (“Moon Jar”). Can you talk a bit about these particular themes and images and how they draw you, or how you are drawn to them?

DJ: My previous husband died in July in Florida. It is unbearably hot there that time of year. Then, as life would have it, I fell in love with someone who lives (as I joke) virtually in Canada! As you know, here in Vermont we experience six months of winter, more or less. This, for someone who had lived forty years of her life in Florida, was quite a shift. In my mind, my love for snow is a projection of my love for my new husband. And actually I have learned to love the cold, cloudy, moody days of winter and what we call a spring here. Sometimes now the sun is just too much for me, too harsh, too oppressive.

The natural world plays a huge role in my work and I have been drawn to observing nature, whether it be the heavens or the moths at the window, ever since I was a child. We have a cabin in the Green Mountains National Forest where I like to go to write. If I have a light on inside, inevitably the moths come and cling to the screen outside. They are hard to ignore! So they end up as metaphors in my poems. So too do birds! I feel like a child learning the new northern birds and forest trees in my new home.

LN: The series of poems in the center of the book is titled “Rakomelo,” a word we had to look up and learned is the name of a Greek digestive spirit used as traditional home remedy for coughs or sore throats. It’s clear that your time in Greece was healing for you. Are there other resonances or reasons for giving that name to this group of poems?

DJ: I went to the Cycladic island of Serifos in Greece a year after my husband died. Rackomelo is a drink that is a mixture of honey and an alcoholic beverage called raki, and it is meant to be enjoyed warmed. We indulged in rakomelo almost every evening. It became a constant in my life when I needed something reliable and stable. Eventually what became that for me was the very person I fell in love with on the island, my current husband, Major Jackson.

LN: The first line of “The Morgue” (“They say evening will come”) reminded us of Jane Kenyon’s “Let Evening Come,” which so beautifully evokes the sense of letting go and trusting that peace and comfort will come. Was that poem in your mind when you wrote your poem?

DJ: I love Jane Kenyon’s work so much! I have read her poems over and over. I have also read her letters to Hayden Carruth and the memoir Donald Hall wrote about her inevitable fall to cancer. The line in my poem “The Morgue” is intended to be thought of as a conversation with Kenyon. She is the “they” of my line, a term we often use and attribute to some authority. I feel she is an authority on observing the unavoidable sorrows of life. After reading so many of her poems in which she openly shares her own struggle with depression, I didn’t mind invoking her in my own struggle. But, in “Let Evening Come” she brings the poem to an end with the comfort of God. I don’t think I offer any such comfort in my own poem. The image I end on is almost absurd. Why would a corpse need a neatly folded blanket? What good will it do him? At that point in my life, I was certainly questioning God, faith, fairness, and my future.

LN: Your poems are filled with references to art: the Dutch Masters, Rothko, Duccio, etc. Can you talk a bit about the role of art in your life and poems?

DJ: I taught art history for about ten years in Florida. It was one of the most rewarding teaching jobs of my life! My late husband taught at the same school, and we would take students on trips to New York City from Oviedo, Florida, every year to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Frick, the MoMA, the Guggenheim, and the Brooklyn Museum of Art. He taught history and often had the same students as sophomores before I got them as juniors and seniors. In a way, I came to see the world mainly through the lens of various artists and art movements.

To me, the landscape of Maine matches that of one of Rothko’s paintings, and as I stand looking out to the ocean from the shore his work comes to my mind immediately. The Mérode Altarpiece at the Cloisters offers an intimate interior view of a fifteenth century Netherlandish home and an image of Mary reading (a book of hours, of course) with her hair casually undone… relaxed… just before a huge life-changing event is about to take place. Any life-changing moment speaks volumes to me. Such quiet moments in visual art amaze me. But, then again, almost all visual art amazes me. I can spend an entire eight hours of a day in a museum, and I have! I have also been known to create summer travel entirely around seeing one particular piece of art (The Isenheim Altarpiece in Colmar, France or the Mosque at Cordoba, to name just two). Thank you for asking about the art references in Moon Jar.

The title work comes from the Korean notion of accepting imperfection. When dealing with life after suicide loss, a part of me will always be scarred or deformed, but like what artists found appealing about the process of making the moon jar, we learn to live with and love that imperfection. If we can do that with ourselves, we can begin to do that with others! All of this is visually manifested by a piece of ceramic art, which is why it speaks to strongly to me.

LN: Throughout Moon Jar, there is a contrast between warmer locales such as Italy, Greece, and Florida and colder locales like Canada and Vermont. How do geography and place influence your writing? Do you bring a notebook with you and write when you travel?

DJ: I do tend to write about the new physical landscapes I visit, or at least I try to. And I’ve had the luck and privilege to travel extensively. I make it a point to learn specifics about the particular places I am in, even if it is temporary. It isn’t completely accurate if I were to say that I only experienced pain and loss in warm environments and that the snow and cold were my only safe spaces. I slowly came back to myself while on the beaches of Greece, and fell into my new husband’s arms there and in Italy too. Both Italy and Greece definitely feel more familiar to me in terms of temperature, but snow is now a new love for me.

I am genuinely super excited to learn the new world in which I find myself (Vermont’s Green Mountains). Chickadees, woodcocks, maples, birches, aspen, winter mix, snow flurries, woodchucks, moose, even chipmunks all excite me to no end. My friend Kerrin McCadden mentioned to me how fun it is for her to watch my excitement over birds and animals that she takes for granted having lived in Vermont her whole adult life. I have a favorite hike that I like to keep secret where my husband and I climb for about twenty minutes towards an open field with a panoramic mountain view, then sit and look and listen and write for as long as we can stand the cold in the winter or the bugs in the summer. We go year-round. If someone would have told me ten years ago that I would enjoy sitting still in 17-degree weather, I would have told them they are crazy!

LN: The poem "Slip" stands out as quite different from the rest of the poems in Moon Jar. Could you walk us through the creation of this poem?

DJ: Well, it came as a poem that I wrote before one of our poetry group meetings. I have a window near my writing desk through which my cat Obi likes to go in and out. All year round, might I add. So, as I was beginning a new poem, I watched him truly slip out the window. After I wrote that as my first line, I found that I really liked the “s,” “l,” and “p” sounds in the word slip and wanted to repeat it as the last word in every line. Then I asked myself the question, what else slips?

Unfortunately that led me to remembering how my late husband actually took his life. I’m sure you wouldn’t be surprised if I were to say that so much, on a daily basis, reminds me of that moment. The lines in the poem in which I reveal the details of the suicide are surrounded by other rather mundane moments of slipping in life: a pencil slipping when writing a particular letter, the tongue slipping when mispronouncing a word, the sun slipping behind a cloud, and my worst fear here in Vermont of slipping on ice. In that way I reveal (and I hope successfully) the tension between our daily lives and occasions of tragedy.

LN: Which forthcoming books are you most excited about right now?

DJ: I am excited to read poet Tess Taylor’s book on Dorothea Lange called Last West that is a companion to the MoMA’s current exhibition on Lange.

Other poetry books that are recently released or forthcoming that I’m excited about include Ledger by Jane Hirshfield, In the Lateness of the World by Carolyn Forché, 13th Balloon by Mark Bibbins, Pale Colors in a Tall Field by Carl Philips, Come the Slumberless to the Land of Nod by Traci Brimhall, Seeing the Body by Rachel Eliza Griffiths, Obit by Victoria Chang, Kontemporary Amerikan Poetry by John Murillo, A Nail the Evening Hangs On by Monica Sok, Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalie Diaz, Atomizer by Elizabeth Powell, Keep This to Yourself, a chapbook by my friend Kerrin McCadden, and of course The Absurd Man by Major Jackson!

I am also super psyched to read Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir by Natasha Trethewey and Bad Tourist by Suzanne Roberts, forthcoming in the summer and fall respectively.

LN: What is currently bringing you peace?

DJ: Natural spaces have always brought me peace. I am so fortunate to be surrounded by the greening mountains of central Vermont as I answer these questions. I am taking pictures of the wild flowers like red trillium, yellow trout lily, and bloodroot as they emerge from the deep dark earth. That brings me so much joy!! That and birdsong… and trying to guess the birds.

Photo by Gabe Emilio Cortese

Didi Jackson is the author of Moon Jar (Red Hen Press, 2020). Her poems have appeared in The New Yorker, New England Review, Ploughshares, and elsewhere. After having lived most of her life in Florida, she currently lives in South Burlington, Vermont teaching creative writing at the University of Vermont.