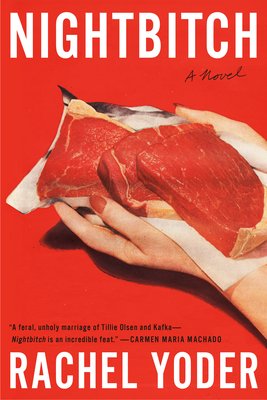

Recently we invited the fabulous Vermont poet Megan Buchanan to introduce the Literary North audience to a writer she loves. We are thrilled to share Megan’s interview with her friend Rachel Yoder, who wrote one of the most talked about debuts of the year, Nightbitch, published in July 2021 by Doubleday.

The writer Kevin Wilson says about Nightbitch, “I could not love a novel more than Rachel Yoder’s Nightbitch. It’s such a uniquely brilliant book, one that looks at the intersection of motherhood and art, the terror of “a thousand artless afternoons.” And it is so wonderfully observant, so precise, and yet manages to expand and expand upon those initial concerns, turning magical, dark, and funny.”

Congratulations, Rachel, on your fierce debut!

Megan Buchanan: You’ve been working hard as a writer throughout all the years I’ve known you. When we met in Prescott, Arizona in 2008, I remember how we coincidentally had work “touching” each other and back-to-back in the same issue of The Sun Magazine—my poem, your story. That got my attention. I know there have been other earlier book projects, and I am wondering how Nightbitch became The One, your firstborn-into-the-world book. I ask because I’m curious, but also thinking of this Literary North audience, specifically, because so many writers read this newsletter.

Rachel Yoder: Wow. Well, there’s a whole shadow story to Nightbitch. I had a collection that was a mass of stories I pulled together from my two MFAs but was not a group of stories I had written to all go together as a collection. It was a good-enough collection of short stories. They were going to be published by this small press in Chicago, and the editor there was very generous and kind and edited the whole manuscript, then introduced me to an agent. She wound up leaving for another press, and it came out the small press had done a lot of its authors wrong in terms of payments and royalties, so I ended up pulling it. It was the right thing to do, but it was sort of a big heartbreak of a project where I was deep in my Nightbitch years, deep in my isolation, deep in my not-writing, deep in my anger, and I thought I was going to have this book to pull me out of that. And it fell through, and this was really soul-crushing. That’s part of the shadow of Nightbitch.

During this time, I also applied to the State of Iowa for the Iowa Arts Council Fellowship, saying I was going to finish up this short story collection. I wound up getting it in 2017 and with it came a grant. That grant is the only way that Nightbitch is here with us. I literally took that money and I walked over two blocks to this hippie daycare in a big house. I walked in desperate. I was alone during the week. The guy that runs it is this man named Tim with a long, wizard beard, and you can’t call there and get any answers—you have to go there and catch Tim in person. The place is sort of chaotic, they eat outside, you know, it’s this wonderful place. So I caught Tim, and I said, I’m a writer and I haven’t written since my son was born, and I just need, like, two or three hours a day. I have an amount of money, and I want to give it to you. I want to bring my son here. Can you take him? Can you fit him in? Of course they were full. Cohen was about three. But he said he could help, and the price he quoted was insanely affordable. And that’s how it started. I was overly bonded with Cohen because it was just the two of us together 24/7 all week when my husband was away working. At the daycare I would have to hand him to someone. He’d be sobbing. He wouldn’t let go of me. It was horrible. The whole year, every day; it never got better. I would peel my son from my body and go home and write, or not write or cry or take a nap. But I had finally figured out a way to give myself at least two or three hours of psychic space a day. I finally found a space where my creativity could live, where I could be with my thoughts. Nightbitch was my way of writing myself up out of it.

MB: I’m thinking about how your experience relates to Biden’s economic package, subsidizing family leave and daycare, that could potentially provide some spaciousness, financial and/or schedule-wise, to women and families.

RY: There’s something to be said about female creativity, not just women who are artists. Women, especially mothers, having the psychic space to be happy and find their joy outside of mothering.

MB: So your son is across the street with the wizard guy for a few hours a day. How did you let this wild story rip on out?

RY: I didn’t let it. In a lot of ways, it felt like something that existed separate from me, though obviously it came from a primal part of me. The first 50 to 70 pages were not written, so much as they were channeled. They just came out. I don’t normally have that sort of writing experience. I think what facilitated that channeling is that I was very in touch with my rage, in sort of a scary way. In a way I knew if I didn’t do something with the rage, I would self-destruct. It also was channeling the rage a lot of women were having after the 2016 election. PTSD rage where our worst nightmare has been voted into office.

MB: Yes. Millions of people voted for him.

RY: It was so demoralizing. I was having conversations with my artist friends: what do you do when you are so angry and so demoralized? I don’t want this to make me go even more into my silence. The book is an act in the face of that. A fuck you. Writing has always been my way of getting myself out of my worst psychological quagmires. I knew I had to do something with it—Nightbitch is where it went. It was my way of redirecting my rage towards this creation of something artful. At the beginning I was just writing for myself, a desperate, artistic act. And if no one else ever read it, that was fine with me. It was urgent.

MB: As I read the book, I kept thinking about how the way society is set up leads to such a sharp imbalance in labor for women. I lived for a couple weeks over the summer with another family. The other mother also lives in a house of all male people. I was so grateful to share the driving, the cooking, the coordinating and figuring out and remembering all the things, the vigilant watching of kids playing in the ocean—and I eventually felt a deep nervous-system reset. Happiness was the result of feeling that support. Nightbitch captures how women have to hold all the details: the daily work, the planning, the schedules. Society is not set up to support women.

RY: The funny thing about writing the book when I was so angry, and Nightbitch was so angry, was I kept having the sense of Who can she rage at? Her husband isn’t a monster. It’s the sense that she is raging at these systems of which she is a part, and it’s infuriating that that is the thing you’re angry at because you feel so powerless to change it. It’s so big. Societal systems are so huge and already in motion and it would take so much to stop them and make them move in a different way. And so what do you do? What do you do in the face of these big things you’re a part of that seems like they are never going to change?

MB: Let’s talk about Nightbitch’s husband. (I’m so glad there were those tiny little hot sex scenes in the book. Thank God for that!) He does eventually kick into gear and begin to be more involved with household tasks and childcare. She navigates how to ask for more specific support and he does hear her.

RY: That might be too easy of a turn in the book. But the place I arrived at, which is kind of a hard place, and the place that Nightbitch arrived at, is that no one is responsible for your own happiness but yourself. If you want your life to look differently, that is within your control to a certain point.

MB: I am thinking about race and class in the book and in our lives as writers. The privilege we both have is glaring. We are both super educated and white, we have healthy kids, we bought houses somehow, our parents love us. We have health insurance. Women do hold so much, and our lives can be hard, but when you add racism or the fear that your black or brown child could be hurt or worse into the mix, that is a different level of holding while having to stay fully engaged in life’s tasks, let alone embody the psychic space to create art. But black and brown women do create art and thrive in a society built strategically to block their flourishing. Nightbitch is living with a certain set of pressures that create the rage, which is hers, yours, mine, but I am wondering if you have had conversations with women of color about the book.

RY: That’s another thing, the conversations have been very white. I did talk with Amerie, a pop singer, of all things, who also has a book club. (And it just so happens we also went to Georgetown together many years ago and even had a sociology class together. But that’s beside the point.) We did not talk about race directly, but I did talk about how my work as a mother is to raise a son who is cognizant of his privilege as a man, as a white person, and doesn’t take it for granted. And I am curious if you are a black reader—or trans or a man or a person without children or what have you—if the book is resonating in some way.

MB: Have men been reading it?

RY: Yes, I do hear from men, and I am always surprised to hear from men. Sometimes it is from the point of view of I relate to this actually as a father, in my fathering. Or most of them say, Wow, I really understand my wife more. Men need to read it, husbands.

MB: That was my thought very early on as I read the book: men need to read this.

RY: My husband did not really get it until he read the book, and he didn’t say much about the book after he read it, but his actions have changed a lot. Now he comes home (on weekends) and he just takes over. He does everything without me asking. I am still angry about the years he was absent. I am trying not to keep tally and be resentful, but that’s where I am.

MB: How does your son perceive your new fame?

RY: We were at the pharmacy the other day and he said, Does she know about your book? And I laughed and I said, No, the pharmacist does not know about my book. Somehow he was thinking about that. I told him, This is a book about how much I love you and how much you changed me. And I told him that there’s going to be a movie, and there’s going to be a Coco in the movie.

MB: I have to ask about the book-within-the-book, the Field Guide to Magical Women. I loved those sections—such an important, sparkling thread within the novel. I love how the Field Guide places Nightbitch within a community of women, lessening her experience of isolation.

RY: I love a book within a book. I love the formality of a wise narrator, and I love playing around with texts that sound very authoritative, but are saying deeply mystical things. Ostensibly it’s an academic text, but the topic is mystical ethnography which is ridiculous. To use this voice of authority to speak about the bird women of Peru! So that was really fun for me, but also to be inspired by some of the most resilient women that I know, like you.

MB: Are other entries other people you know? I was so honored to find myself there (a True Blue). Thank you!

RY: Let me think! Not really. I asked myself, are any of my friends magical women? And I thought, if any of them are, it’s Megan Buchanan. First of all, she talks to trees….

MB: Actually, trees talk to me!

RY: And you’re just so embodied, your experience of the world and how you express yourself.

::

Literary North: Thank you so much, Rachel and Megan, for this conversation.

Rachel Yoder is the author of Nightbitch (Doubleday), her debut novel released in July 2021, which has also been optioned for film by Annapurna Pictures with Amy Adams set to star. She is a graduate of the Iowa Nonfiction Writing Program and also holds an MFA in fiction from the University of Arizona. Her writing has been awarded with The Editors’ Prize in Fiction by The Missouri Review and with notable distinctions in Best American Short Stories and Best American Nonrequired Reading. She is also a founding editor of draft: the journal of process.